. . .

They take him, two to each arm and three to his body, and they drag him off to the Land of Pleasure and Happiness.

. . .

“Under the surfaces of things,” proposes one sorcerer sagely, “there is probably some sort of undersized farmer who causes things to make sense. That is why the living are living and the dead are dead; why all things have their enemies; why one thing is right for one person to do, and a different thing is right for another; why jaguars fall, but sorcerer-sages propose things sagely, rather than the other way around.”

They study their star charts. They project the future.

“Such a farmer cannot endure indefinitely,” argues Hunyg. “Because if a farmer could live forever under the surfaces of things, then that in itself would not make sense.”

. . .

The Mayan sorcerer-sages consider Hunyg’s proposition.

“It’s true!” agrees Ahpop-Achi, or possibly Mochcouoh.

(I am not completely clear on everything that happened at this conference, on who said what, and all the like. Sometimes I think that the Mayan sorcerer-sages might not even have been speaking English.)

(But somebody says that, anyway.)

“That poor farmer,” sighs Hunyg. “Cursed by his own efficiency.”

. . .

Pacal considers the consequences of the world making sense because of the farmer under the surfaces of things.

“But then,” says Pacal, tugging on his ear, “when that farmer dies, won’t the world revert to its former, lower-energy state under the pressure of a cavalcade of apocalypses? Won’t the world stop making sense again, and unravel all of space and time and history, and not all the jaguars nor all the sages to have ever meant anything at all?”

. . .

“And is it better for the community of Mayan sorcerer-sages,” Pacal wonders, carefully, “if the world is such as to make sense, and mean things, and have value, and thus to facilitate the study of prophesy, the cosmos, and the stars, or if the world is not such, but is rather a playground of sorcerers, where those of great will and clever concepts can dominate all mortal things?”

“The latter,” answers Mochcouoh — I am certain, on this occasion. “But in this case we must concede the advantage.”

“Why?” asks Hunyg.

“We cannot do otherwise,” says Mochcuouh. “We are prisoners of our own sagacity.”

. . .

And one by one each of them comes around to this same position, in the privacy of their souls: that they would rather have a world where the seasons turn, and the cosmos is knowable, then a world where power over the unknowable is theirs.

. . .

And so, like all those who love the world must eventually do —

Under the burden given unto men and women of reason, in this life —

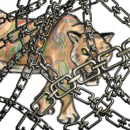

They round up a handful of jaguars. They enchant them with great spells. They launch them, after the fashion of the sorcerer-sages of the Mayans, into a decaying orbit around the world.

. . .

The seasons turn. The years go by. And, just a tiny bit faster than the turning of the Earth, a handful of jaguars fall.