– 1 –

Deep under the world is Hans, who first made sense of things. Hans, who built the world from chaos. Hans the smith; Hans the farmer; Hans the dwarf.

. . .

Hans loves the world. He doesn’t live in it.

He keeps his farm in the cavernous darkness, under the surfaces of things, instead.

His farm is beneath the centipede that writhes inside the world. It is past, and under, the Great Gate. It is past and beyond the bridge where march the soldiers of the dead. It is not all that far from Hell.

. . .

If you were to go to visit him you would have to find your way past all those things, and past the Weave-wid too, and many other dangers; but when those trials were behind you, you would find yourself in a realm of gentle, rolling hills and growing things and among the houses of the svart-alfar, where certain fairy-tale things survived.

You would walk then their roads and taste possibly of their grapes and marvel at their wonders and the triumphs; and there you would find Hans’ farm, too, with its stone in many colors, its caves and its grottos, its fields and its artificial sky.

Each morning there a sun-bird rises.

It bursts from Hans’ sun-bird eggs. It tears free of its enclosure. It plummets upwards. It strikes its head against the stalactites of the caverns, cracks its head open, bursts into flames, and gives over the roof to glow.

This fades eventually into night.

. . .

The night, near Hans’ farm, holds only shining echoes and memories of the morning’s madness. Crystal veins throb with subtle luminance. Butterflies flutter, flicker, glow. The slime of the moon-beast’s fur has taken in the sunlight; it reflects it, slowly; it doles out that reflection, in gleams and glitters and pale shimmers, through all the hours of the dark.

It is a beautiful farm but it is a doleful farm for the things Hans does are bad.

. . .

It is bad to write blank checks to a wallaby.

Oh, Hans, it is bad.

It distracts the wallaby from the things of its life. It makes the wallaby perplexed. It has no place in its mind to hold the checks, and one too many options in its flesh. It is not ready to be rich, not that wallaby; Hans has ruined it; and if one day it should fill out and cash those checks a terrible accounting is sure to come.

. . .

Again: it is bad to sharpen a goat.

It is all right to sharpen the cheese of a goat. I cannot say why you should or why you would but if you do or if you’ve done then I am sure that it shall be all right. If you’ve wanted a particularly sharp wheel, for instance, or a tangier flavor — that’s fine.

But do not sharpen the goat itself.

. . .

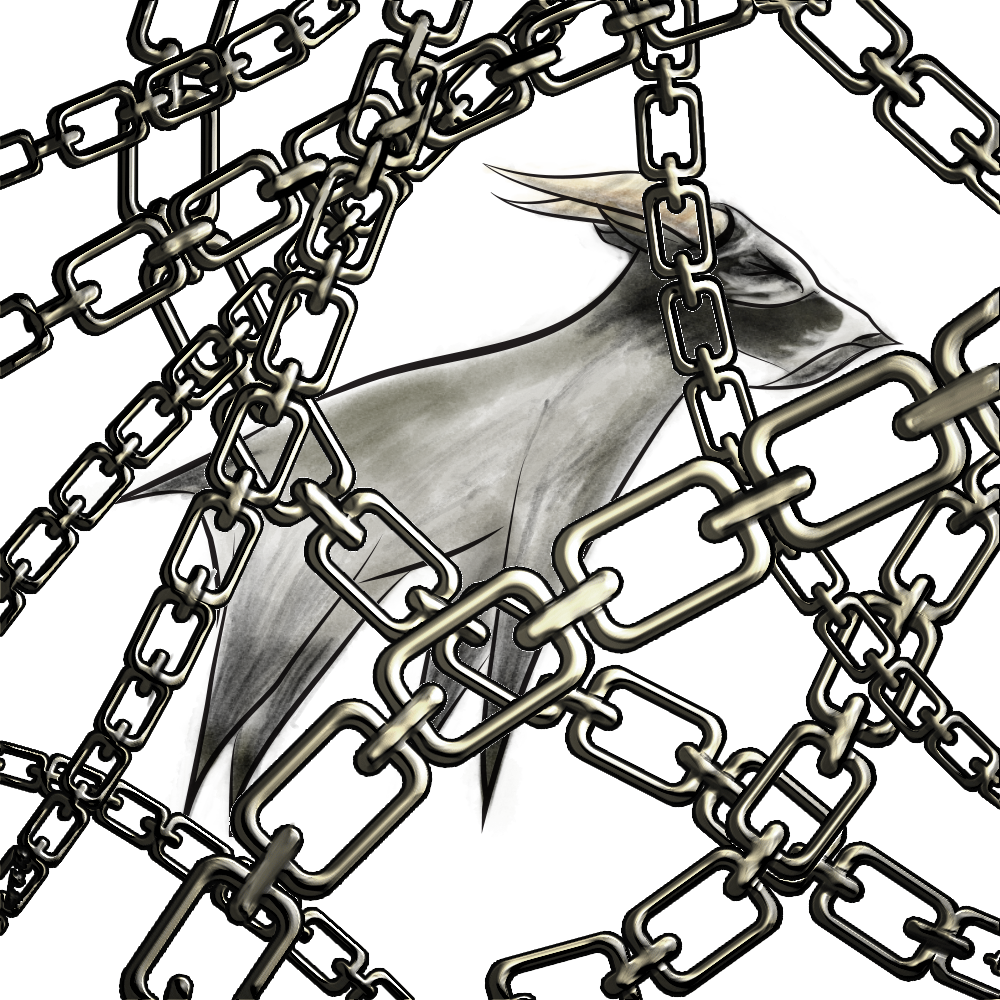

It is down there, now, below there, now, Hans’ goat. It is sawing, sawing, sawing on the bars that make its pen.

It is tossing its head now, it is cutting the wooden boards of its enclosure’s ceiling with its great sharp head. Then it is back to its principal work. Its eyes gleam with goat-wroth — with that fey, hircine obsession with their own sharpness that is given to certain goats. It is sawing, sawing, sawing on the steel bars that are its cage.

. . .

Maybe this goat thing is not on Hans. He tapes his own emus, after all, but the goat is sharpening itself.

Only — he doesn’t have to keep it there, in its enclosure in the dark. He doesn’t have to imprison it, and that imprisonment is what makes it sharp.

If he hadn’t caught it, if he had not kept it, then it would have killed its way across the continents. It would have been the pike-goat, the sene-goat, it would have slaughtered thousands and left its tracks across the earth, but then some dull bear would have gotten it, some hero, some champion. It would have ravaged but it would have died, before it had grown so sharp as this.

. . .

It’s not a good goat.

Listen:

It’s not that I want it to ravage the world, or to have ravaged the world. It’s not that I think it should have been loosed to be a sene-goat, or even that I think that it should be free at all. And I certainly don’t think that Hans has the right to just . . . kill it or whatever, just for being atypically sharp.

I don’t even know what it is that I think that Hans should actually have done.

I just know that if he had left the goat free, then it would have divided its time between sharpening and ravaging. It would have been a hundred times, a thousand times, duller than it is, and most probably also dead. It is precisely because he has chosen to imprison it, to pen this goat, to keep it there, to keep it bound, that it is sharpening itself and nothing but sharpening itself for every minute of every day.