Title Page

Enemies Endure: Book II

The Storm that Saw Itself

by

Jenna Katerin Moran

Copyright © 2010-2013 by Jenna K. Moran

All rights reserved.

All characters in this story are fictitious or heavily fictionalized. Readers are advised against drawing conclusions about or regarding persons living or dead based on this material.

Portions of this material have appeared previously on imago.hitherby.com

Special thanks to:

Karl Friedrich Borgstrom, for teaching me the joy of sailing

Dedicated to:

Cync Brantley

Rand Brittain

Hsin Chen

Cheryl Couvillion

Anthony Damiani

John Eure

Jim Henley

Jim Hermann

Miranda Harrell

Elane Imgoven

Paul M. Johnson

R’ykandar Korra’ti

Angela Korra’ti

AJ Luxton

Kevin Maginn

Robin Michael Alexander Maginn

Killian James Sebastian Maginn

Gregory Rapawy

Gretchen Shanrock-Solberg

Alexis Siemon

Amy Sutedja

Chrysoula Tzavelas

and

Raymond Wood

– 1 –

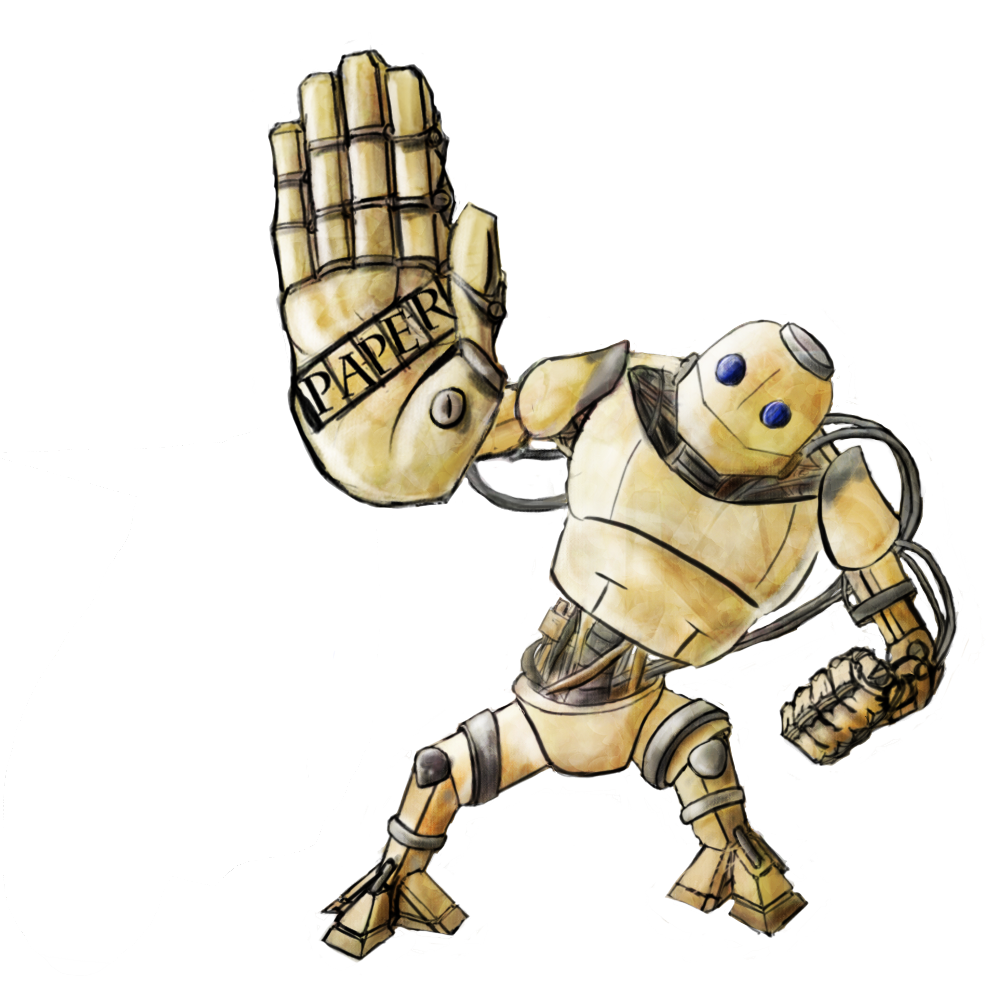

One summer, when Emily’s eyes have gone all-over gold and she has been given over to the Keepers’ House, she sits on the hillside with Eldri and his amazing rock-paper-scissors-playing robot Navvy Jim, and Eldri tells her stories of the beginning of the world.

He tells her the story of Hans.

“A long time ago,” Eldri says, “when the world was chaos, and you could hardly stir a pot without a fiend arising from the turmoil or a horror clawing down to eat your face, there was a svart-elf named Hans, and his eyes were purest gold.”

“Really? Like mine?”

“Like yours,” Eldri says. “Oh, that wasn’t totally unusual or anything. Any svart can —”

Here he ponders. He closes his eyes. He opens them. He stares at Emily and there is a ring of gold around his pupils, and then his eyes drink her in, they loom large around her, they hold her as if she floated between the Earth and the Moon.

She giggles at this. She twists in her mind and writhes away and slips down to the ground, as if to land from flight on the wet grass of the night; shakes off the vision, and is staring at her godfather (whom she calls uncle, incorrectly) across the room again.

“— but it’s rare for it to be so complete, so unrelenting, so always-on. His mother knew he was something special, and his father drank a lot and rode around on underground dragons.”

“That’s poor parenting,” Emily criticizes.

“It was a chaotic time,” Eldri concedes. “In fairness, his mother only really managed three or four years with Hans herself before she flew away on a gigantic red bat.”

“Wow,” Emily says.

She flits up to her feet. She hugs Navvy Jim, who looks at her in perplexity. Then she sits down again.

“He was a svart-elf, of course,” Eldri says, “So he could manage pretty well on his own, particularly with three or four full years of a mother’s love. He went around doing this and that and finally realized, ‘you know, this world’s a pretty crazy place. It’s just this sea of impressions that’s constantly giving rise to abominations. But wouldn’t it be better if things had reasons? If questions had answers? If you could look this way and that and everywhere there’d be a reason why?’”

“That’s silly,” says Emily.

“Is it?”

“Well,” Emily says, “if things didn’t have answers, how could he bother asking questions?”

“That’s a good point,” Eldri says, “I suppose. I certainly don’t think anything did answer him, when he asked those questions. So there’s that! . . . But there might have been a cave cucumber or something that he talked to. I don’t know. The stories are kind of ambiguous when they’re talking about stuff that’s all the way back then. Maybe his Mum flew by on her bat, or his Dad had hiccupped out a boozelemental or something caparisoned in shell and trident that answered him when he asked; but if anything like that had happened, nobody’s ever said to me.”

“Mm,” Emily says.

“So he built the world,” Eldri says. “He tamed it. He stomped it flat, as it were, although I guess that technically he stomped it round.”

“That was good work!” Emily says.

“And there were still monsters,” Eldri says. “Horrors. Awful world-devouring things. They hung out around the edges of his construction. They were what was left over of the wild, you see. Gorgons, you know, and the nithrid, and drownéd Pepsi, and the like. You could even say — they were awful things, they were world-ending things, they were monsters, because they were what was left over of the wild that came before. Because if they were the kinds of things what fit into the world Hans made, then they would have done; but instead, they didn’t. So he locked them up, bound them, trapped them, killed them sometimes — though that was bad,” he asides.

“You can’t?” Emily says.

Navvy Jim looks over. He says, softly, “It makes the world much less.”

“Mm,” Emily says. “But what if it were a hundred-handed monster that was always throwing rock, paper, and scissors?”

Navvy Jim’s eyes light with soft amusement. “Or a young girl throwing ‘whale?’”

Emily, who used to shake up the rules of rock-paper-scissors in just that exciting fashion, tightens her lips. That’s a burn, she admits.

“Hans took,” Eldri says, “everything that didn’t fit, and he caged it in the earth, or wrapped it around the stars, or wove it through the sky, or even tied it through itself. He set toads to glower at it, or turned it into gold; cut off a foot sometimes, taught stupid mind-devouring riddles to it, whatever. All day, all night, he was down there in the depths of the Earth, trying to pin down the chaos and make it bland. And he kept waiting for it to get easier, you know, particularly once you really had a world to live in, once you had your continents and your seas and even some kind of order to the underworld beneath; he kept waiting for stuff to settle down and for everything to just be good, but it didn’t, it never did. He kept working on that until the very end; until the scissors fell.”

Emily thinks about that.

“In the Keepers’ House,” she says, “we say — I mean, in our inside voices, but still — that Gotterdammerung will come.”

“Yes.”

“That we can hold it at bay,” Emily says. “That we can stand in creepy circles around people and push it back. But it’ll still come. It’s too late for anything else. The world’ll burst.”

“Well,” Eldri says, “Hans died.”

“The world can’t burst,” says Navvy Jim.

“No?”

“I won’t allow it.”

“That’s a brave robot,” says Eldri.

“You can’t stand in creepy circles around people,” Emily says. “You’re a rock-paper-scissors-playing robot.”

“I will have to stop the bursting of the world by playing rock-paper-scissors,” Navvy Jim agrees.

– 2 –

In those days gods walked among us, courtesy of Konami Corporation.

There were two of them arguing right in this spot—

Right over there, in that blasted pit that not even the repavers can heal.

– 3 –

It was seven years before that summer, back when the world still seemed like it might have hope; although it’s still happening, you understand, it’s always happening, it’s always been happening and it always will happen, I think, because that’s just the way it is.

It goes like this.

There’s a cat curled up on old Mrs. McGinty’s porch.

There’re crows croaking raucously on a nearby power line.

Margerie walks up from the south. She doesn’t look around. She finds a square of sidewalk and she sets up her Konami Thunder Dance pad.

The crows go silent as death.

She plugs her pad into a PlayStation 5 and an uninterruptible power supply. She kicks off her shoes. She steps up onto the pad.

The cat uncurls. It stretches. It lopes away.

Now old Kalov comes clicking down the road from the north. He’s got his game under one arm. He’s using the other hand to hold his cane.

He sets up his dance pad.

He plugs it in, just like Margerie’s.

He steps on. And smugly, because it’s allowed in the University’s Konami Thunder Dance Club rules, he rests his cane tip beside his feet on the dance pad.

“Kalov,” says Margerie. “Don’t be stupid. You can’t beat me.”

Kalov doesn’t crack a smile.

“Maggie,” he says, “It’s the decision of the Konami Thunder Dance club that we’re going to upgrade to the new version. It’s a good version. It’s a better version. It has improved spiritual harmony. It has contextual help menus. It has over 181 new songs.”

“But it’s dishonest,” says Margerie.

“You’re a good dancer,” Kalov says. “Don’t ruin your life.”

The air is as clear and still as glass. The sun isn’t moving.

That’s the way it is with Konami Thunder Dance. They could stand there all day, if you’ll pardon some linguistic ambiguity, and the sun wouldn’t move one inch.

But Margerie just shakes her head.

She doesn’t let it sit like that. She moves her foot to the side, just sweeps it across what Konami calls the “keyboard of the feet,” and she’s hit the Symbol for storms.

There’s lightning in the sky.

And Margerie says, “It ain’t the true thing any longer if we do this. It isn’t the Konami Thunder Dance, if we do this, given to us by God. It’s just a — pathetic corporate sell-out.”

“You’re too inflexible,” Kalov complains.

“Konami doesn’t care about us,” she says. “The original team’s all gone on to work for Round Square. They’re just squeezing a few more Euros from the newbs.”

It’s raining.

“Lois Lethal’s dead, Maggie,” Kalov says. “The Kid is dead. They were buried alive.”

Scissors had fallen from the sky one day, sextillions of them in a swarm from space, all wicked metal and great scissors-mind and twin gleaming blades on every pair. Scissors had fallen, strange though that may have been, and in that rain the dancers had died. Dozens of them — dozens of the best of them: not cut, they were immune to cutting, they couldn’t be cut while the power to their PlayStation was on, but they’d drowned, they’d died, they’d been buried in the piles of metal that fell from space. And if it had stopped there, people would’ve just blamed the scissors, but it hadn’t.

Like he’d said.

A landslide took the Konami Kid. Lois Lethal went down a well. And even Ren the Bing —

“Do you want to die?” he asks her, raw.

Because that’s how it is, when you dance the Thunder Dance.

That’s the genuine thing.

If you’re good enough, if you’re only good enough, or maybe it’s actually only if you’re just too good, then one day the Earth will open up and swallow you. Or you’ll get trapped in a mine cave-in. Or something else. Something else will happen and it will bury you alive —

That is the Konami Thunder Dance, as it was given to the world by God; that is how it is, or how it was, anyway, at least.

— until the patch.

“You think you can just do that?” Margerie says. “You think you can just go into the high scores coding and set LIVE_BURIAL to FALSE and change the plans God made for this mortal world? Just how arrogant are you, Kalov? Who the Hell do you think you are?”

He glares at her.

“I’m the faculty advisor for the thunder dance club,” he says, and he clicks his cane, and the Earth groans and the sun goes black.

“I was breakdancing in Los Angeles when you were in diapers,” he says. His voice is cold and even. “I was playing Dance Dance Revolution when you were just a chit. I broke X2 and In the Groove, Maggie; I danced too well for them. And I was dancing the thunder dance, I was shaping the world with its designs, even before the scissors fell. God’s plans, Maggie? You think I care about God’s plans, Maggie? He can ask me mine.”

It’s pretty cool. He thinks. He thinks it sounds pretty cool.

But Margerie just smirks.

“Don’t see you getting buried, sir, for all that boasting of yours,” she says. “Maybe God just doesn’t know that you’re alive.”

He’s going to say something more. He knows he is. He feels the word-wroth coming to him.

He’s going to think of just the perfect thing to say any second now.

But he doesn’t get the chance.

She is like God; she does like God; she presses the power button with her toe.

“There’s no turning back now,” warns the voice of the machine.

And for Margerie and Kalov alike the patterns of the Konami Thunder Dance begin to flow.

There are one hundred and sixty-eight distinct “keys” on the Konami Thunder Dance pad, divided into eight regions. Eight-key sequences, properly timed, combine to form a Symbol. Most of these sequences have four to seven redundant versions, leaving approximately 1.25 x 10^17 combinations. Each Symbol generates a unique effect; each Symbol hacks the world; but with 10^17 of them, and more, most of the possibilities of the game remain undiscovered even by the greatest masters.

Each Symbol of the Thunder Dance is one thing, exactly, for all its many parts; one thing, and one thing only, save, perhaps, for the cheat code Dynamite.

The greatest thunder dancers can make manna to feed the starving. They can bring peace to the harrowed heart.

Theirs is the power to warp the world.

They dance to Freezepop and Lauper, then; she dances Flight and he dances Time; and it is for this reason, it must have been for this reason, that Ipswich has always hung (and will always hang) above the Earth.

And to the theme from Goldeneye she dances of duality and he dances of faces.

And this is the last of the truly great thunder dances, I think, save, perhaps, for one. The sea writhes with their dancing and burning waves crash down upon the shore. They roust out wolves to chase the sun and moon. The sky rains blood and flowers down upon them and they crack it open to show the hidden light that shines beyond.

But she is slowing.

She does not understand it. Not at first. She is slowing. Her thoughts are clouding. She kicks the Symbol for Clarity, even though it costs her points — it’s not a big feature of Yatta!, to which she is dancing — but it does her no good.

She is better than he is, but she is slowing down. It is like there is gelatin around her. It is like it is setting around her, closing in around her legs —

And finally she understands.

She curses him. She howls curses at him, she blasts at him with honeyed lightning and she calls up flames, she doesn’t care any longer that the Symbols don’t fit the song she’s dancing to, she only tries to kill, and kill, and kill, and finally, she slumps.

Yatta!

He’s downloading it.

Onto her PlayStation — he’s downloading it. Its network light is on, on his and hers. He’s downloading the patch right onto her machine.

She misses one step. Then another. Finally, she’s just sitting there, watching the patterns and Symbols float by her until she fails out of the dance.

“Damn you,” she says. “Damn you.”

She powers down her machine.

“Damn you.”

“That’s settled, then,” he says. “But it’s all right, you know. It’s good. And you won’t have to die.”

She sits there. She is crying. She is broken.

He tries to comfort her. She drives him away. She hits him. She screams at him. He draws back.

“You’ll understand,” he says. “Once you’ve played the new one. Once you’ve tried it out.”

But she doesn’t.

She doesn’t turn on her PlayStation 5, or any other PlayStation, again.

It is an age of gods; they walk among us, courtesy of the Konami Corporation.

But they are smaller, now.

– 4 –

This story is about Mr. Enemy — I’ve said that before — but I want to talk about Emily for a while instead. For this book, just this one book maybe, I want to focus instead on Emily and the storms; on Emily and the lightning, Emily and the dynamite, Emily and the Keepers; to talk about Emily, who loves jaguars and yellow hats and Eldri, and most especially Navvy Jim.

Only, Eldri is dead now, he got eaten; and Navvy Jim is dead now, I think, I mean, I’m pretty sure; and the jaguars that Emily cares for most —

They spin around the Earth, in the cold blue emptiness of space.

It’s kind of cool and it’s kind of cruel because they don’t ever get to breathe.

I don’t think I could do it. I don’t think I could look at a jaguar and say, “You know, one day, jaguar, the whole world’s going to fall apart. So I’m going to launch you into space and you will fall for millennia around the world and you will be cold and you will be airless but I will charge you with my sorcery to protect the life that breathes and flourishes below.”

I don’t think I could do that to jaguar Chan or jaguar Ixchel or even to jaguar Yohl.

And I know Emily couldn’t have. I think. Because I’ve seen her when she thinks about the jaguars. I’ve seen the way she goes distant, and her face goes soft, because they are to her — I think they are a symbol of her inspiration to her, or of her hope. I think that ever since she was a child and she met the jaguar Bahlum, who fell to Earth, she has thought that the jaguars are the most beautiful and magical thing out there anywhere; that they teach her when they move, in and through that movement, that there is a thing that is beautiful and moving; that life is joyous and in motion; that it is OK, that it is somehow OK, that the world is so full of suffering and trouble, that it is OK that life is so very hard, because there are things bigger than that, more beautiful than that, more fiery and vast and glorious than that, in a long decaying orbit around our little mortal world.

She could fall into despair, I think; she could drown in it; and then she could look up, and she could point at the jaguars, and the light of them would take her. It would flow through her, and the darkness and the ice and the despair in her couldn’t hold. Despair is a stillness, you understand? It is only there in stillness. It ceases when there is motion. It breaks when there is life.

And she would look up at the jaguars, right through that awful shadowing, and she would say:

O See Them Move!

And the dark would burst.

That is what they are to her. That is what they mean to her.

They are not that to me.

Me, I think I kind of hate them because they are the doom of Emily, who is my friend.

They are magical and beautiful, anyway, the magical jaguars. They go around and around the world. It’s kind of cool and it’s kind of cruel, and they are cold, and they miss the air.

And if what she’s going to do works, if what she’s going out there to do now works, and she calls them down, then they’ll probably just land on her, or something, because they’re jaguars, and that is what jaguars do.

They will fall on her. They will be burning.

You know how jaguars can be.

They will land on Emily, and they’ll rake her back, and maybe they’ll even eat her some or set her on fire, and she’ll be lucky if she survives.

And then the scissors will fall again, afterwards, and they’ll trash the house and get stuck in all the trees. And the Fan Hoeng aliens will land and they’ll disembark and they’ll say “Take me to your leader,” only there won’t really be any leaders left, so I’m expecting that they’ll get a little tetchy about all that. And Peter will stagger out of his Fan Hoeng cell, where they’ve been keeping him, I guess, and he’ll be all mean and he’ll punch people because he’s Peter, ’cause even if he’s a saint of sorts I’ll bet he’s gotten back his punchy hand.

What she’s doing is going to be a total catastrophe, I mean, pretty much all of it, but the worst part will be that whole thing with the jaguars, because I don’t want them to land on Emily and kill her. It is a thing that I do not want to see.

She’s basically —

I mean — I mean, there’s hardly anybody left.

But that’s not the way she looks at it.

The thing she says is this:

“It’s about time,” she says, all smiling, “I figure, that they all came down: that jaguar Yohl, and jaguar Ixchel, and jaguar Chan, and anyone else up there who’s been fighting for us so very long and so very hard and without any air to breathe, gets to come down and take a breath on Mother Earth.”

So she’s going to dance the Thunder Dance, and the Earth will shake, and the jaguars will come down. And patch or no patch, and Navvy Jim or no Navvy Jim, when the jaguars and the scissors fall they’re going to bury her alive.

– 1 –

The svart-elf Saul finds a puppy. Well, three puppies, really. Or maybe it’s a three-headed puppy? It isn’t really clear. Saul raises the puppy but then he has to abandon the puppy because the sugar fairies drag Saul off to the land of pleasure and happiness.

It’s OK, though.

Hans’ll take care of that puppy for him!

Hans puts the puppy in his pot. He melts it down. He turns it into a treasure hoard of poisoned white wolf-gold.

This is why you should never loan your puppies to Hans.

The thief-hero Vaenwode, perhaps unsurprisingly, would like to have a lot of gold. He travels under the world. He steals a third of Hans’ great hoard. He takes it back up to Earth. Unfortunately for Vaenwode the gold creates a secondary manifestation: a magic wolf becomes a part of him, wound in him and through him, and makes him a very hungry thief indeed.

The svart-elves Eldri and Brygmir go up to the surface. They extract the wolf from him. They bind it. They fetter the wolf’s limbs and maw with a cord made from the footfalls of a cat, the arms of a four-armed ape, the torment of the willing, the bearing witness to the wrongness, the spittle of a bird, and the perseverance of hope. They seal the wolf to Vaenwode and his family, wind it in him and within him, through him and with him, and nevermore to be apart.

Now Vaenwode has one (1) Fenris Wolf!

This does not do him very much good. At first the wolf is his friend but then it is his enemy. At first the cord is comfortable on both of them but later it becomes an atrocity. The cord does not grow with the growing wolf; it cuts suppurating furrows into its legs and snout instead. In some places you can see through to the bone. As for Vaenwode, he is eventually eaten and the wolf passes down to his daughter Jordis; and her son, and his son, and his daughter, and her daughter, and so forth.

It passes eventually into the keeping of the modern Mr. Gulley, owner of the Lethal Corporation, who decides that it must die.

The wolf believes, based on a feral intuition, that the cord is finite: that it will not last forever; and more than that, that the one destined to break the cord and free the wolf is young Edmund Gulley, Mr. Gulley’s son.

Mr. Gulley becomes obsessed with the wolf. He commits an indiscretion. Fearing that the cat’s footfalls in the chain of the wolf will fray, he buys a new set from the smith-dwarf Joffun. These the dwarf affixes to the feet of the household cat, Inedible, who becomes clanking and rather consternated thereupon. In trade, Mr. Gulley gives Joffun young Edmund Gulley’s heart.

Joffun is overcome by the potential of the heart. He becomes drunk. He dances in the streets and rants about the magic he will work. He waves a fresh and bloody young boy’s heart over his head. This proves to be inadvisable behavior in a country quite so well-policed as post-cisorian England; Joffun is apprehended, tried, and imprisoned, and the heart returned to Mr. Gulley and his son. Mr. Gulley places it in a box on Edmund’s desk: at first a box made of straw and then later (when the wind of the wolf’s breath caves the straw box in) a sturdy case of mahogany, balsa wood, and teak.

– 3 –

Thon-Gul X, the incarnate wicked god of space, hurls an extremely large swarm of scissors at the world. They fall from space, in some places piling up to twelve feet high.

Humanity survives but is somewhat traumatized by the experience. People switch from using scissors to using “trissors” — the non-traumatic three-bladed trissoring solution.

Even the classic game rock-paper-scissors acquires a deviant and degenerate cachet.

Jaguar Bahlum fights the scissors. This perturbs his already decaying orbit. He falls burning to the ground. Later he is caged near Bibury and Emily sees a jaguar for the first time. This excites her a great deal and she tells her mother, “Mommy! Mommy! Jaguar!” which should be understood as a shorthand for the complex of various emotions that I have described above.

Later Thon-Gul X sends a giant world-killing meteor at the Earth, and — just in case anything survives both rock and scissors — the evil rock-paper-scissors playing prophet, Lucy Souvante, also a space princess assassin from the royal line of the alien Fan Hoeng.

– 4 –

Turtle-people tie Betty to the stake. They burn her.

If I had to explain what was wrong with the world, with Hans or without him; if you asked me why there are wolves and scissors, why there are evil prophets and killer nannies, why there are cruelties and thefts and suffering and wicked gods —

If you asked me why the world needs fixing —

I would trace it back to this. To Betty’s burning.

Things were always pretty bad on Earth, you know, what with all the genocide and the torture, but that was the moment when it just plain became completely obvious that the world was gone all wrong.

The turtle-people don’t mind it, though, not really. They don’t even seem to care.

They just laughed and danced, as if to say:

Where is your theodicy now?

– 5 –

The rain of scissors brings about the death of Hans, who hammered down the world into the shape of sense. On that day Jeremiah Sandiford transcends; his heart is made pure and his hands correct. On that day, conversely, young Linus Evans of Sussex falls into despair, knowing in an instant that there will be nothing good in all his life.

Jeremiah will become Jeremiah Clean, or “the cleaning man.”

Linus will become the antichrist.

Amelia Friedman, who is a renegade alchemist, discovers that her son Tom is destined to destroy the world. The young science adventurer has parasitic ophidian DNA grafted onto his own; he will one day go all snaky, warm the world, eradicate the human plague, and replace Earth’s dominant species with his own.

This seems to her to be an awfully lonely destiny, so she resolves to find other children like him and bring them into her home.

She adopts the antichrist Linus Evans. She invites young Edmund Gulley over to play. When she discovers that a young girl named Jane is living with a sun-eating wolf and has a possible destiny of destroying the world, herself, she interferes with the government’s plans to kill them both; using a combination of alchemy and influence, she has a shadowy government Agency kidnap Jane instead. These four children, and their cat Mouser, form the science adventuring “Doom Team,” whose motto is “You don’t have to die just because some people think your existence is evil.”

Eventually Amelia Friedman vanishes, their space princess assassin nanny Maria Souvante attempts to kill them all, and the Doom Team falls apart.

Jane, who’d survived Maria’s death ray by becoming a Taoist immortal, shuffles through a series of increasingly baroque and terrifying foster homes. She winds up living in Ipswich with Martin, a mysterious boy.

Tom investigates his mother’s disappearance but meets “the cleaning man” instead.

He emerges from the meeting human — his fate cut off, his future cut off, even the ophidian DNA in him swiffed right off his genes. Tom, feeling like he can no longer have science adventures, goes through a muddled and confusing time; but after an unpleasant and nearly-deadly encounter with space princess assassin Lucy Souvante, he rejects the idea of being normal and dabbles instead in the forbidden things. From the substances of dead hats, in the cemetery of the hats, he makes a graveyard hat, a corpse hat, a hat to make him better at hat-making. His early experiments are damaging: his guidance counselor tries on one of Tom’s hats and becomes first homicidal and then lethally apoplectic. His roommate Stephan tries one on and is broken. But the hats are addictive, or possibly woven through with destiny; Tom cannot, or at least does not, stop. The better the hats he makes, the better the hats he can make; the better the hats he can make, the better the hats he must make; and so he scales up towards hatpocalypse until at last he has built the final hat, the kether-hat, the crowning hat, a hat to be an answer to his original forbidden dream:

A hat to straighten its wearer’s inner fire, to refine them; to take a scattered and divided and mortal soul and concentrate it into a single pure and shining light.

He lowers it onto his head.

From that moment he is no longer Tom the science adventurer, at least, not exactly; nor Tom the moping milliner’s brat.

He is crowned Thomas the First, instead, head boy of the House of Dreams.

And Edmund is home with his father; and as for the antichrist, Linus Evans —

The government and the Papacy lock him up.

– 6 –

The sun-devouring wolf is dead. It was nuked — that shadowy government Agency that had discovered it, that had kidnapped Jane, dropped nuclear weapons on Bibury to contain it, and thus was the end of the wolf named Skoll. However, you cannot kill all your giant wolves with nuclear weapons.

The notion — well, it’s risible!

Mr. Gulley creates a school — the “Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth” — instead, where his son Edmund, and others, will be trained to combat existential threats to humanity and most specifically to kill Fenris Wolf.

– 7 –

Saul looks back from space and he weeps for the fate of his puppy; he abandons hope, then, gives up on sugar fairies and on paradise; and dies, that he may be born again on Earth.