– 3 –

Thon-Gul X, the incarnate wicked god of space, hurls an extremely large swarm of scissors at the world. They fall from space, in some places piling up to twelve feet high.

Humanity survives but is somewhat traumatized by the experience. People switch from using scissors to using “trissors” — the non-traumatic three-bladed trissoring solution.

Even the classic game rock-paper-scissors acquires a deviant and degenerate cachet.

Jaguar Bahlum fights the scissors. This perturbs his already decaying orbit. He falls burning to the ground. Later he is caged near Bibury and Emily sees a jaguar for the first time. This excites her a great deal and she tells her mother, “Mommy! Mommy! Jaguar!” which should be understood as a shorthand for the complex of various emotions that I have described above.

Later Thon-Gul X sends a giant world-killing meteor at the Earth, and — just in case anything survives both rock and scissors — the evil rock-paper-scissors playing prophet, Lucy Souvante, also a space princess assassin from the royal line of the alien Fan Hoeng.

– 4 –

Turtle-people tie Betty to the stake. They burn her.

If I had to explain what was wrong with the world, with Hans or without him; if you asked me why there are wolves and scissors, why there are evil prophets and killer nannies, why there are cruelties and thefts and suffering and wicked gods —

If you asked me why the world needs fixing —

I would trace it back to this. To Betty’s burning.

Things were always pretty bad on Earth, you know, what with all the genocide and the torture, but that was the moment when it just plain became completely obvious that the world was gone all wrong.

The turtle-people don’t mind it, though, not really. They don’t even seem to care.

They just laughed and danced, as if to say:

Where is your theodicy now?

– 5 –

The rain of scissors brings about the death of Hans, who hammered down the world into the shape of sense. On that day Jeremiah Sandiford transcends; his heart is made pure and his hands correct. On that day, conversely, young Linus Evans of Sussex falls into despair, knowing in an instant that there will be nothing good in all his life.

Jeremiah will become Jeremiah Clean, or “the cleaning man.”

Linus will become the antichrist.

Amelia Friedman, who is a renegade alchemist, discovers that her son Tom is destined to destroy the world. The young science adventurer has parasitic ophidian DNA grafted onto his own; he will one day go all snaky, warm the world, eradicate the human plague, and replace Earth’s dominant species with his own.

This seems to her to be an awfully lonely destiny, so she resolves to find other children like him and bring them into her home.

She adopts the antichrist Linus Evans. She invites young Edmund Gulley over to play. When she discovers that a young girl named Jane is living with a sun-eating wolf and has a possible destiny of destroying the world, herself, she interferes with the government’s plans to kill them both; using a combination of alchemy and influence, she has a shadowy government Agency kidnap Jane instead. These four children, and their cat Mouser, form the science adventuring “Doom Team,” whose motto is “You don’t have to die just because some people think your existence is evil.”

Eventually Amelia Friedman vanishes, their space princess assassin nanny Maria Souvante attempts to kill them all, and the Doom Team falls apart.

Jane, who’d survived Maria’s death ray by becoming a Taoist immortal, shuffles through a series of increasingly baroque and terrifying foster homes. She winds up living in Ipswich with Martin, a mysterious boy.

Tom investigates his mother’s disappearance but meets “the cleaning man” instead.

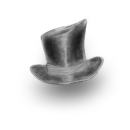

He emerges from the meeting human — his fate cut off, his future cut off, even the ophidian DNA in him swiffed right off his genes. Tom, feeling like he can no longer have science adventures, goes through a muddled and confusing time; but after an unpleasant and nearly-deadly encounter with space princess assassin Lucy Souvante, he rejects the idea of being normal and dabbles instead in the forbidden things. From the substances of dead hats, in the cemetery of the hats, he makes a graveyard hat, a corpse hat, a hat to make him better at hat-making. His early experiments are damaging: his guidance counselor tries on one of Tom’s hats and becomes first homicidal and then lethally apoplectic. His roommate Stephan tries one on and is broken. But the hats are addictive, or possibly woven through with destiny; Tom cannot, or at least does not, stop. The better the hats he makes, the better the hats he can make; the better the hats he can make, the better the hats he must make; and so he scales up towards hatpocalypse until at last he has built the final hat, the kether-hat, the crowning hat, a hat to be an answer to his original forbidden dream:

A hat to straighten its wearer’s inner fire, to refine them; to take a scattered and divided and mortal soul and concentrate it into a single pure and shining light.

He lowers it onto his head.

From that moment he is no longer Tom the science adventurer, at least, not exactly; nor Tom the moping milliner’s brat.

He is crowned Thomas the First, instead, head boy of the House of Dreams.

And Edmund is home with his father; and as for the antichrist, Linus Evans —

The government and the Papacy lock him up.

– 6 –

The sun-devouring wolf is dead. It was nuked — that shadowy government Agency that had discovered it, that had kidnapped Jane, dropped nuclear weapons on Bibury to contain it, and thus was the end of the wolf named Skoll. However, you cannot kill all your giant wolves with nuclear weapons.

The notion — well, it’s risible!

Mr. Gulley creates a school — the “Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth” — instead, where his son Edmund, and others, will be trained to combat existential threats to humanity and most specifically to kill Fenris Wolf.

– 7 –

Saul looks back from space and he weeps for the fate of his puppy; he abandons hope, then, gives up on sugar fairies and on paradise; and dies, that he may be born again on Earth.

Hermetic Mysteries

It’s impure. It’s an impure situation. There’s this Department of Esoteric Studies, and once upon a time the cruel demiurge would vomit up cash and grants and all manner of free sodas to keep it in operation, only, now . . . it doesn’t.

“I can’t take up the slack,” says Mr. Gulley. “I don’t mingle my gold with demiurge business.”

He’s afraid of the demiurge getting under his skin.

It was corrupted. The whole academic environment was corrupted, you understand? Money had come in and taken it down. Money had turned it from this thing where kids get to grow up and become better, become heroes, become people who fight off wolves, into this thing where a teacher can’t afford to walk out across the demiurge pits and go to the grocery and buy cup ramen and poison for their students any longer.

The lightbulb god is underfunded and goes out.

The third and seventeenth hermetic mysteries are lost.

And the final paperwork comes in, you know. The thing that says: that’s it. You’re out. It’s all done. Corrupted. Tarnished.

And here was the miracle. Here was the alchemical mystery, the magic ladder, the holy tree. Thatcould stick that paperwork in the middle of that diagram, and hold it under the light of Saturn, and purify those flaws away, and turn that final paperwork into funding.

The aqua regia was effective.

The impurity was cleansed from stuff, and now there is funding, bright and gold.

“But where does it come from?” people ask, like there’s an answer. Like funding comes from somewhere. But here’s the secret. Here’s the alchemy. Here’s the mystery. Funding’s like gold, like purity, like perfection.

It doesn’t come from somewhere.

It is a thing that arises. It is a manifestation of the will; of hope; of dreams; of choice.

That and the light of Saturn, of course, and the aqua regia, and the proper diagrams, which is why, if you’re still undecided on your career path, Esoteric Studies is the definite and proper choice.

– 1 –

A snake-wroth falls into the primeval ocean. It stirs up the sediment and invents DNA among the silt. This dissatisfies it. Life is inadequate to it.

Eons slip by while it cultivates itself beneath the waves.

The snake-wroth folds itself up eventually into a serpent. It writhes. It surrounds the world. It laughs at the life that throngs upon the land and in the waters and it wraps itself around the planet to split the sphere of it in twain.

In this it fails.

Heroes strive against it. They fight. They die. Then one succeeds; a hero kills it: drives a spear of raw Unmaking through its heart.

It tastes the face of the girl who slew it.

It is cruel what she has done; it is unforgivable; but it forgives her, anyway, because her tears are salt.

– 2 –

Aunt Linnea shows young Cheryl origami. She folds a boat. She presents it to Cheryl. She has Cheryl hold the mast. Then she has Cheryl close her eyes.

There is the sound of paper folding and unfolding.

Linnea has Cheryl open her eyes again.

It is magic. It is a miracle. Cheryl is no longer holding the sail, but the hull.

“Show me!” says Cheryl. “Show me! Show me!”

And — and after much teasing and many refusals — Linnea does.

– 3 –

A long time ago a storm saw itself and in that seeing became a nithrid. It became a thing of the divine fire; it lashed the world about with itself, it shattered cities, it danced and it changed the world with its footsteps and it laughed at the doings of the svart-alfar and all humankind.

This proved to be a mistake.

Hans caught it up. He burned a cow and used the fire of a cow to bind it. He whisked a duck and used the ghost of a duck to bind it. It is bad to whisk a duck, but he did it; bad to plug in a cow, but he did it; bad, or even worse than bad, to gather lint from a sharpened goat —

He made a chain for it, anyway, bound it up, and lid it into a nithrid-hole on Hans’ farm, deep beneath the world; on Hans’ farm, under the surfaces of things.

He caught it. He immured it.

And for many years it dwelt below in misery and in chains.

Eventually Hans’ power waned and the nithrid worked itself free.

Now it is small. Now it is weak.

Free, yes —

But so very weak.

It is staggering through thorny passages. It is bleeding as it goes.

It is weak and it is chained and it is being called.

The nithrid has taken on a human shape. Each heartbeat hurts it. Each heartbeat, the storm in it — the furious, city-shattering lightning that is the nature of it — pulses against the chains Hans set around it. The ghost of a murdered duck, metal from the pearl in a human eye, cow-fire and sheep-fire and the keel of a sky-wraith’s boat — they’ve all been cunningly woven around it, and even now, even now that it has pulled free of Hans, even now that Hans is dead, the chains still hold it back.

There is a delicate pulse at its wrists. At its throat.

Its color, that should be the argent of lightning, is darkened and muted to the color of a human’s skin.

It reaches the surface, finally. It has taken it a long time.

It crawls up along a ledge, and suddenly there is a ladder. It has missed the transition between the depths of the world and the human underground; preoccupied with its pain and with the calling, it has wandered straight into the sewer without even noticing the change in state.

A thrill of excitement runs through it.

It will run up the ladder, lightning on the metal. It will burst the manhole, pop free as lightning and storm along the streets. It will light up the buildings, make them dance St. Vitus’ Dance, and chase and slaughter the men and women that it meets. It will swirl up and down and all about in great gusts of lightning and —

Its chains compress it painfully.

It huddles in on itself. It whimpers around its chest. Then, rung by rung, the nithrid begins to climb.

Mr. Gulley meets it at the top of the ladder. After a momentary hesitation, because the nithrid is caked in filth and a ratty dress, he reaches down a hand to help it up. He pulls it to the side of the street before a car hits it.

It can feel the following:

There are chains wound through Mr. Gulley, too, chains and wolf-gold, and the nithrid’s bonds are at the other end. They are tied together by the commonalities of their imprisonments. The world is still all fettered, it is still all bound down, even though Hans himself is dead; and the nithrid has been pulled up the last few miles, the last few years of its long ascent by Mr. Gulley’s tugging at their conjoined chains.

Mr. Gulley is on the phone.

The nithrid admires Mr. Gulley’s phone. It watches the signal. It touches some of the data, twirls it around its finger, until he waves irritably in its direction and it desists.

He finishes his phone call.

He puts the phone away.

Then he looks the nithrid up and down.

“You’re a deadly threat to the world,” he says. “You’re the kind of storm that could ravage everything, aren’t you? Leave it burnt and in ruins? Dance through the sky and drive the humans back to huddle in caves and transcendent fear. You are that savage beauty, called the nithrid — am I right?”

It stares at him. Then it smiles, slightly. It is a feral look.

“You are the one who called me.”

It touches his arm. It looks him up and down. It sees the wolf-gold in Mr. Gulley’s eyes.

It says: “Are you going to free me, puppy?”

Mr. Gulley shudders.

Then he laughs. It is sudden, painful. It is as if his breath hurts him as her own hurts her. “I wish I knew.”

The nithrid studies him.

“I offer you this,” he says. “I am no god to wish you free and bring down your devastation on the Earth. I wish I could want such things, but it’s not in me. I am no smith-dwarf, neither, to bind you tight and lid you in a hole beneath the Earth. I am only a man, a man with a wolf, a wolf bound to me and through me, in me and within me, and around it an awful chain. If you do not stop me, I will affix you to that chain; it will seal you to me; and I will use you to my ends. And if that bond breaks, as I’m told it will, then —”

He hesitates.

“Then I suppose I will have loosed a nithrid too onto the world.”

The nithrid breathes. It looks at him. Then its heart beats twice; a smile crosses its grim face; and it sees what he does not:

That he has been given unto her, she nithrid, not to be a burden but to be a gift.

It says: “Tell me what I must do.”

“Take a shower,” says Mr. Gulley. “Can you shower? Please tell me that a shower will not short you out, or cramp your chains, or destroy you. You smell like poo.”

“I can shower,” it says.

“Then you will go to the Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth,” says Mr. Gulley, “and I will enroll you as a student there; and you will learn to walk among us, and of the murdering of wolves.”

– 4 –

Origami frustrates Cheryl. From the beginning to the second year of practice, it is only a joy to her; but then, when she has mastered the basic techniques and some of the art of it, she becomes frustrated. Her fingers are too clumsy, but more importantly, her mind is incomplete.

There is something that she sees that she cannot fold. Blind spots in her cognition interfere when she goes to make her work. The beautiful beginning and the perfect ending are clear to her but they do not connect; at one, two, three, and sometimes even four places in the middle, four nodes, four interstices — they do not work.

She constructs plans but they are not practical.

She folds but she cannot make.

Sometimes she tries to bridge the gap with trissors. This produces a nameless yearning in her and a nameless fear; she stares at the third blade of the trissors as if it is alien to her. She is too young to remember proper scissors. She does not know what it is that her world has lost.

She thumps her head down on the table after one false attempt.

She sobs, twice, before she masters herself.

“This is silly, Cheryl,” she says.

She does not know that she will one day be as God. She does not know that she will one day make that final fold, and take command of the destinies of the world; nor that this shall be the death of her to do.

“It’s just paper,” Cheryl says, in self-reproach, and she goes out.

She goes down to the sea. She is eleven years old and her mind is dancing with patterns, folds, shapes, twists, and shadows. She sits on a rock. She sees how she could fold the rock, then the place where she would fail to fold the rock — in part, she observes, because the rock is stone and not just brown paper, but also because there is an inconsistency in her design.

She tastes the salt air of the sea.

She sees the serpent.

The sight rises her. It is not her rising: rather it is as if the sight of the snake has possessed her. It has absented her from herself, it has turned off her governance over herself, it has folded it around a corner of her mind and into an inaccessible corner of herself, it is not Cheryl who is the subject of Cheryl walking to the snake but the sight of it; not her endpoint that is the object of that action, but Cheryl herself.

Perhaps we could say it like this:

Circumstances walk Cheryl to the sea.

She stands beneath the great swaying head of the serpent. She looks up. She stares into its eyes.

It is vast and it is paper.

She knows it. She recognizes it. It is folded in her and through her, within her and without her. It is a part of her. It is a thing she has been trying, so foolishly, and without knowledge of it, to fold for this past year.

It is paper folded into a chain of snakes, and then that chain folded in itself and through itself, into a geodesic pseudo-sphere; and the links of paper do not end at the vertices of it but connect that sphere to others instead — to billions of others, uncountable others, all held together by their characteristic bonds and into a greater shape.

And where did such a thing come from? In what manner did it arise?

You could say: circumstances folded it into a snake, or the snake folded itself into being, but neither is quite correct. Say rather that it is a snake-wroth, a paper-wroth, a folding-wroth. This can happen. Sometimes an irrational snake-like pattern falls into the sea. There it invades the ocean’s currents, its coral reefs, its crabs, its fish. There it possesses the silt of the bottom, the salt and the waters, sometimes even the sea air.

The snake-wroth winds through the ocean: it is in it and within it, through it and about it. It twines these things together. It uses the sea as the medium for its fruition.

It exceeds human work, though it resembles it.

It is origami —

But not such origami as humans know. Not in ten years, not in ten hundred years, not in ten thousand could the gathered nations of the world have folded such a beast. The techniques might exist — though, then again, they very well might not — but there would simply not be time.

And yet, as she looks at it, Cheryl recognizes that she has been trying to fold it.

That she herself, she Cheryl, has been infected by the wroth; by:

Let such a snake be born!

It has a stomach, folded out of paper, that serves no other purpose than to turn its meals into paper — it is a pulping stomach, not a digesting one; a folding stomach, complete with heaving paper cilia that make origami of their own.

It is waxed.

How is it waxed? There is some other part of its inner engine, doubtlessly, for this: to devour and convert the creatures of the sea in all their bulk and poison into wax, or perhaps into some subtler laminate, lest the snake become soggy, fall apart, lose the subtleties of its knots and folds, and turn into the white caps of the sea.

It moves.

It sways above her. It extends to the horizon, and as it moves it seems to breathe, all through its structure. The cells of it fold around the holes that honeycomb it. They compress. They expand. It is a living thing.

She stares.

Now Hans had not been absent in the construction of the snake. He had not let such an awful beast grow on his world and be unmarred. Surely had he done that, had he let it be, it would have wrapped itself tight around the world by now, squeezed it, broken it, shattered it half and half and then broken up the pieces, claimed its destinies, pounded the stone and life of it into paper for its de-planeting, broken the moon, seized up Mars and Venus and all the rest of them, and finally torn up the sun — eventually to chain through all the cosmos, if the vast space-ness of it did not confound it, as one great waxed and woven thing.

This thing it did not do.

Instead Hans infiltrated himself into its construction. He twisted it. He folded up the folded snake; added his cruel design to its subtle folds. He has looped the snake-wroth like a Möbius strip, like a Klein bottle — it’s hard for me to know for sure just how complicated the geometry here gets — so its inside is its outside and its head its tail. The strands that make up one end run diagonally through the gaps that make up the other, so that in the moments between each breath, Cheryl can see the head draw taut — be drawn taut, perhaps — and become the tail, its eyes smoothing out and its jaw clamping shut, before it is released and flows out to become the head again. She can see the serpent trying to look at her, its Cheryl-wards end trying to hold on and stay a head for longer than its structure would naturally allow; the strain of that causes knots of disruption to run down the length of it like the knobbed pull-chain of a lamp.

It is always chewing itself, tasting itself, biting down on its own tail-meat in the moments of its transition. It is always blinding itself and un-blinding itself. Its stomach is always writhing, reconfiguring, and becoming lungs: each breath it chokes for a moment on its recent meals. Its lungs are always writhing, reconfiguring, and becoming its stomach: each breath, for a moment, it is digesting air.

It is horrible that someone would ever do a thing like that to a gigantic paper snake.

If it were not so very large an unexpected sympathy would seize up Cheryl’s heart in an instant. Instead she is simply lost: how can this be? How can something like this be?

She holds up her hand. She reaches to it.

She caresses it with the flat of her hand.

It occurs to her as she touches it — as she sees its brain dissolve for a moment, a knot pulled through it, and become a long flat muscle, then revive itself with a shudder of paper folding; as she feels the paper rise and fall under her touch — that it wants to die.

It pulls itself down around her. It wraps around her like a thousand circling paper-chains. It lifts her up, so gently, with its breathing form, and there is paper all around her and in every direction; it is circling, it is marvelous, it feels as if the world has let her go, but she thinks that perhaps it has eaten her. What with the nature of the thing, with its inside being its outside, it is very difficult to tell.

She grasps for a handful of the snake, but it is oddly elusive for something that is holding her: for a moment she touches it, then there is a folding, and her hand closes on the air.

It is like riding in a cloud: the soft white waxed expanse of it supports her, but when she grasps at it there is only mist.

The heartbeat of the snake is doubled: it goes this way and that, she hears it, she feels it.

The gaps in the snake are eyes: they surround her: she hears its vast and cavernous thoughts:

You are born to be my enemy, it says. So I have come to you.

I hurt, says the snake. I hurt.

Help me to die.

She is an eleven-year-old girl. She is not yet as God. She does not even know what she is supposed to do. She tries to hug the snake but she cannot hug the snake and even when she gets sort of close to successfully hugging the snake, it does not die.

She punches the snake. She makes a fist and she punches the snake, but paper just wraps muckily around her fist.

If people still played rock-paper-scissors — which they don’t, of course, not after that —

She might have tried to split her fingers into knives, and cut it.

I don’t know if that would have worked any better, but at least she would have tried.

As it is, she finally says, quietly, “I don’t know if I’m your proper enemy, Mr. Snake. Maybe you need to find somebody else.”

So the snake puts her down, gently, on a rock. She’s next to a crab now. It clacks its pincers. It is disturbed by her.

The serpent eddies out to sea.

– 6 –

The nithrid is nervous about attending school. It is an inhuman creature. It is lightning bound down to form. It assumes that everybody will see it and recognize its nature — that their eyes will pierce straight through its human guise and down to its murderous soul. They will point at it and shriek: “There goes a deadly threat to the world! Stop her before she ravages everything, leaves it burnt and in ruins! Tackle her and tighten her chains until she pops!”

Events, to a certain extent, justify her fears.

The students at the Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth are percipient enough to spot her strangeness. They are alert to it: shadows of omen pass across their consciousness when they look at her. They recognize her, consciously or subconsciously, as nithrid.

They simply do not care.

She stands there, wringing her hands, in the quad of the school, and nobody attacks her. Nobody bothers to attack her. They are all too busy or — if not too busy — too distracted, too laid-back, or too lazy to do anything about the world-ending threat that has no idea where to go to schedule her classes or to arrange for a dormitory at her new school.

It is then that she meets Peter.

He is suddenly beside her. His eyes are hard like two bits of flint and his hair is dark but she finds the voice of him oddly warm.

“I don’t like you,” he says. “You’re not natural.”

“. . . no,” she concedes.

He looks her up and down. “You’re also obviously lost.”

“Yes.”

“Come on, then,” he says.

She follows him, nervously. He leads her to the administration building. He asks her, as they go, “Do you like scissors?”

“Pardon?”

“I’m an enemy of scissors,” he says. “If I see scissors, I’ll stomp them! I’ll rip them apart. I’ll throw them in the fire. So if you like scissors, you’d better not mess with me.”

“I don’t really . . .”

He stops. He looks at her. He waits.

“I haven’t had anything to do with scissors,” she says. Then, apologetically, “I was bound in a hole with a duck.”

“How’d you cut your hair?” he asks.

“I don’t cut my hair,” she says. She wiggles a hank of her hair. It darts about like lightning, if lightning were a sandy brown and stuck at one end to a functionally human head.

“I use trissors,” says Peter proudly. “They’re a three-bladed trissoring device.”

“That’s just aces,” the nithrid says.

He takes her to the principal’s office. He pounds on the outside door with a palm. “You go in there. They’ll set you up. Get you classes and a room. I am going to go to class and not care about you.”

“OK,” she says, confused.

“My name is Peter,” he adds.

She opens her mouth. “A nithrid,” she starts to say, but that would be practically giving the game away. She stops herself at “A nuh.”

“Anuh?”

He stares at her for a moment. “Annie? Andrea? Anthology?”

Nobody is named Anthology. I mean, nobody except Anthology is named Anthology, and she is a special case. This book isn’t even about Anthology, so I don’t know why you are thinking about her. She is frozen under the ice! The problem is with Peter’s mind.

“Andrea,” she says.

“Okay,” he says. “I’ll see you around.”

He turns to go. He walks away.

“If I see any scissors,” she says, after him, “I’ll blast them!”

“That’s good thinking,” he says. “But don’t just blast them. Call me! They could have friends. They run in packs, you know. Swarms. Whole swarms of them.”

He’s gone. She blinks.

“Really,” she says. “Scissors.”

She squints a bit. It would never have occurred to that world-ending storm to concern herself about scissors, but now that she thinks about it it is possible that they, like Mr. Gulley, are capable of grounding her.

“Ha!” she says, in vague relief. “Just imagine how stupid that would have been! Burst out, storm across the world, and then get sucked down into the earth by billions of scissors stuck in it!”

This is actually pretty unlikely, but in all fairness, there are alternate timelines in which this was her fate. There are even alternate futures where that happens, although they’re comparatively pretty rare. The Norns weave carefully and cleverly, when they weave our fates, and even such as the lightning must have a care.

Then she goes in and she signs herself up for classes and a room.

She will study the literature of Earth, and citizenship, and basic math; an alien’s guide to study, school, and scholarship; Runes I, Physical Education, and Pre-Combat; and, being the lightning, of course, she takes electives in both electronics and in dance.

– 7 –

Edmund Gulley, Jr., is a lean young man with dark brown hair and a quiet voice. He spends most of his time in silent communion with his wolf.

“It is hard not to eat people,” confides Edmund, to the wolf.

The wolf licks Edmund’s shoulder softly.

It agrees.

Edmund goes to a nearby school. He attends intermittently. He spends a lot of time at the hospital, dealing with complications from his heartlessness or at home, just doing nothing much at all.

Eventually he receives a transfer to a different school.

Edmund leans his head to one side. He stares keenly at his father.

“Really,” he says. “The ‘Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth.’”

“Yes.”

“I have been accused of being evil,” says Edmund. “Or smelly. But rarely wayward. Even vicar Helmsley calls me a mannerly child, you know.”

“I know.”

“And she thinks I’m going to grow up and murder and eat her, too!”

“That’s why loose lips sink ships, son. But I doubt she really does.”

“Children should be seen and not heard,” says Edmund. “I’ve tried to live by that principle.”

“Have you?”

“Well,” admits Edmund, “I’m talking now; but a son may reproach his father, you know, if his father is mistaken. Elsewise, now that you’ve decided that I’m wayward, what option would I have left?”

Mr. Gulley’s lips twitch. He almost smiles.

“Son,” he says, “you had a bit of a fright, with that nanny shooting you; and it’s rough to grow up always wanting to eat your friends. But it’s been a few years now, and if you just stay here sulking, you’ll grow up and you’ll have a kid and the wolf’ll eat you, and nothing in the world will ever change.”

Edmund’s thoughts flicker.

“This is that wolf-killing school of yours,” he realizes.

“Yes,” Mr. Gulley concedes.

“You’re sending me to a — no. No, father. I won’t do it. I won’t conspire against Fenris.”

“Won’t you?” says Mr. Gulley.

Edmund clicks his teeth together. He hesitates. Then he nods. “I thought you’d understood this,” he says. “I thought you knew. I don’t want him to get free and ravage around eating everything, but —”

“But?”

“But he’s Fenris,” says Edmund. “He’s my second heart.”

“I see,” says Mr. Gulley. He stares off into the distance for a while. Then he smiles whitely at Edmund. His teeth are like a set of fangs. “Then I shan’t expect you to. Perhaps you can just learn ballet, or prophesy, then. Or maths.”

“Father,” pleads Edmund.

“Or wolf-killing,” says Mr. Gulley. “But not to kill Fenris. Just, you know, to get you a solid wolf-killing A-level, or in case you’re ever fighting the wolf-demons of the nightmare realm, or whatnot. Best program in the world, son, for wolf-killing, but that doesn’t mean you have to do anything, you know, that you don’t want.”

His smile fades.

“I’m not going to make you,” he says softly. “I wouldn’t. That’s on me, son. You know that. I’d love it if you killed him, but it’s not on you. Not while my heart’s still beating and my lungs are still drawing breath. I just want you — I just want you to know how. In case I don’t make it. In case he eats me, and you’re all that’s left.”

“I’m sorry,” says Edmund. He is looking at nothing in particular. “I spoke out of my own selfish desires.”

“— Son . . .” says Mr. Gulley.

“Best I be about it,” says Edmund. “Then.”

He goes to his room. He packs. He puts on a backpack. He descends the stairs.

“It doesn’t have to be today,” says Mr. Gulley.

“Have you reserved me a spot?” says Edmund.

Mr. Gulley nods.

“And told the school and hospital that I’ll be leaving?”

Mr. Gulley nods again.

“Do we still employ a driver?”

“He can be here in ten,” agrees Mr. Gulley. “I’m pretty sure he hasn’t been eaten.”

Edmund sticks out his hand for his father to shake it. He grins. He can’t even feel his own heart breaking.

“Then I’ll best go be Lethal,” he says, almost as awkwardly as his grammar, and he turns away.

“There’ll be a nithrid,” says Mr. Gulley.

“Pardon?”

“If you need anything,” says Mr. Gulley. “If you need — I mean, I’ve sent people. And a nithrid.”

“How extraordinary,” says Edmund, and he goes out.