– 4 –

There aren’t very many of them.

“Just three of us,” mutters Saul.

They’re gathered in a nook under the stairs. They’re trying to figure out a pattern to the newly-hatted students. If there is one, it appears to be: saints are peculiarly rare.

“This bothers me,” says Saul. He waves his hand at a passing student and prevents them from later getting gout. As an unintended consequence of this outburst of miraculous energy, that student’s grade in English ticks upwards from a C- to a C. “You’d think that saints would be the most common sort.”

“Really?” says Peter.

“Well,” says Saul, “first, consider that we are disparate.”

“Sure,” says Peter.

“But more than that, we’re generically perfect.”

Saul gestures down his front as if to say: I don’t mean to brag, but seriously.

“You’d think more people would be . . . generally well-meaning, wanting to be good, you know, with a kind of diffuse generic impulse towards perfection . . . than dominated by an urge towards science adventuring or cannibalism. I mean, before the hat comes along and refines it.”

“Yeah,” says Peter, “but that can’t be what’s going on.”

“There are not anywhere near that many people with a generic urge towards cannibalism only waiting for a hat to bring it out,” Bethany agrees. “It’d be . . . I mean, there are a lot of scientists and adventurers in the unaltered population, but hardly any proto-cannibals.”

“Meat-eaters?” ventures Saul.

“I’d love a good roast,” says Peter.

“You can’t get to Lethal valedictorian by being a vegetarian!” says Bethany.

“Maybe some kind of inaccurate kerning engine —” starts Peter.

“That’s not the point,” says Saul.

“No,” says Bethany. “It’s not. It’s clearly some other impulse that’s being sublimated into murder and anthropophagous frenzy.”

“Like, the urge to rock a tight outfit,” says Saul.

“Or collect stamps!” offers Peter.

“Or both,” Saul suggests.

Bethany stares out thoughtfully into the hall. “I suspect decorum,” she says, “actually. They are an oddly polite people.”

Saul raises an eyebrow at her. Then he frowns.

“That is a disturbing notion,” says Saul. “Propriety is merely anthropophagous frenzy in a different hat?”

“And when I am blessing people,” says Peter, waving his hand in a generic gesture of blessing out at the hall, “I’m really expressing the pugnacious can-do sensibility of my youth?”

Under some circumstances Bethany would have answered this; but regrettably, she does not get the chance.

The generic blessing, spread too widely, precipitates a phenomenon.

See, even as Peter speaks, there are three members of the House of Hunger coming down the stairs at the other end of the hall. Keen-sighted Bethany has spotted them; Saul feels them coming and is frowning; but neither of them understands their danger in time to warn Peter away.

There is scarred Sally, with her single eye and her loathsome gait. She’s going to grow up to administer surveys one day, but for right now she’s a cannibalistic beast.

There is Lucy, the evil prophet of space. She’d really just planned to take a few local classes in prophesy while the Earth was still around and then destroy it, but now she’s got wolf-hunger wound through her and within her and it’s compromised her intentions. She is chewing on the inside of her cheek and trying not to eat through to the outside of it and remembering what it was like when she was focused on playing rock-paper-scissors with legendary rock-paper-scissors opponents and goats and not on killing and eating people.

Lastly there is Linus.

Linus didn’t expect to get a white hat. He didn’t expect to get any hat at all. He was just hanging out with Tom, getting really, really drunk in celebration of finding one another again, and it turns out that when Tom is drunk enough he will put a magic hat on the antichrist.

It’s a pretty good party game when you’re really drunk, kind of like pin the tail on the donkey, except that you can only play it once.

Tom has basically ruined it for the rest of us forever.

Not even Eldri, who’d made the Ultimate Frisbee robot, who’d made the perfect bingo robot, and even made Navvy Jim —

Even Eldri couldn’t make a robot to play the drunkenly-put-the-magic-hat-on-the-antichrist game now.

Or at least, it wouldn’t ever be as good at it as had been Tom.

Linus’ eyes had paled. He’d fallen over. When he woke, though —

He’d laughed and laughed.

He hugged Tom, who’d tried not to look the least bit afraid while frantically feeling around on his belt for an emergency panic button. He hugged the table and his unfinished beer.

The white dog appeared. The white dog panted.

Linus hugged the white dog and it licked his face.

Then Linus’ vision blurred and the white dog was gone.

“That’s so much better,” said Linus. “I used to have an endless empty hollow in my soul. But now it’s like — it’s where I’m connected to Fenris and to eating people and to the wolf-gold, instead!”

He was laughing and he was crying and it was an absolute and utter relief to him, an end to pain for him, even though in fact nothing at all had changed.

Except that he sort of wants to eat Tom like a steak, and maybe the rest of the bar, stools and vodka and all, now; and he can laugh about that with Edmund afterwards — that’s the good thing, the best thing, the thing that makes it aces, so very, very sweet.

He’s still a boy with a hollow in him, and it’s still bigger than the world, but now it isn’t part of what holds him apart from the world any longer. It’s not a thing of loneliness any longer.

It’s something that brings him and Edmund — and Lucy and Sally and Bernard and all the rest — closer, instead.

So he’s walking with Lucy and Sally, and they’re laughing and talking, and there’s a really good chance that they were just going to walk by the saints without even caring about them, only —

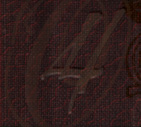

Peter just blessed him, and Linus is, quite frankly, allergic to being blessed.

He sneezes. Vigorously!

“Bless you,” asides Sally.

He sneezes. Vigorously!

“Bless you again!” Sally says, even as Lucy chimes in slyly with a blessing.

“Oh, God, stop,” says Linus, waving and sneezing, which holy utterance causes his tongue to burst into flames.

Linus screams. He begins hitting his face with his palms to try to put his tongue out without actually reaching either of his hands inside his mouth. He appears to be playing the Indian in a quick impromptu game of “Cowboys & Indians,” except (a) he isn’t, (b) he wouldn’t, (c) nobody plays that any more, (d) hardly anybody played that in England to begin with, and (e) his tongue is on fire and he is the antichrist and a white-hatted theoretical cannibal surrounded by two similarly-anthropophagous beasts that are his peers.

Finally Linus begins chewing up large portions of the walls to put out the fire in his mouth. He gulps down most of a priceless painting by Michelangelo that was on loan to the Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth. Damn it, antichrist!

“Ah,” mutters Linus, sinking to the ground, his belly bloated. “That’s ever so much better.”

“Peter,” says Bethany, disapprovingly.

“I didn’t mean to,” says Peter, setting his jaw.

“I think you need to give people more specific blessings,” says Saul. “Like, if I point at him and say, ‘gout, get out!’, well, I don’t think his tongue will catch on fire.”

“That’s true,” says Peter. “That hardly ever happens.”

“We should avaunt,” Bethany says.

“I don’t have any toothpaste,” says Peter, who has no idea what avaunting is.

“I mean, we should get out of here.”

“We could probably beat them up,” Peter says, “non-violently.”

“Let’s go,” says Bethany, but it’s too late.

Sally is standing in front of their nook. She is squinting at them.

“Would you like to be protected from bad weather at sea?” says Peter, because he’s aces at protecting people from bad weather, when they’re at sea.

There’s a long, cold silence.

Then:

“Actually,” Sally admits, “that would be kind.”

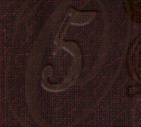

– 5 –

Cheryl is standing on the shore.

Cod and sand eels swim by.

Out in the sea the serpent writhes. It is thrashing in the water, folded, paper, waxed and sealed, and wound throughout itself.

It is eating.

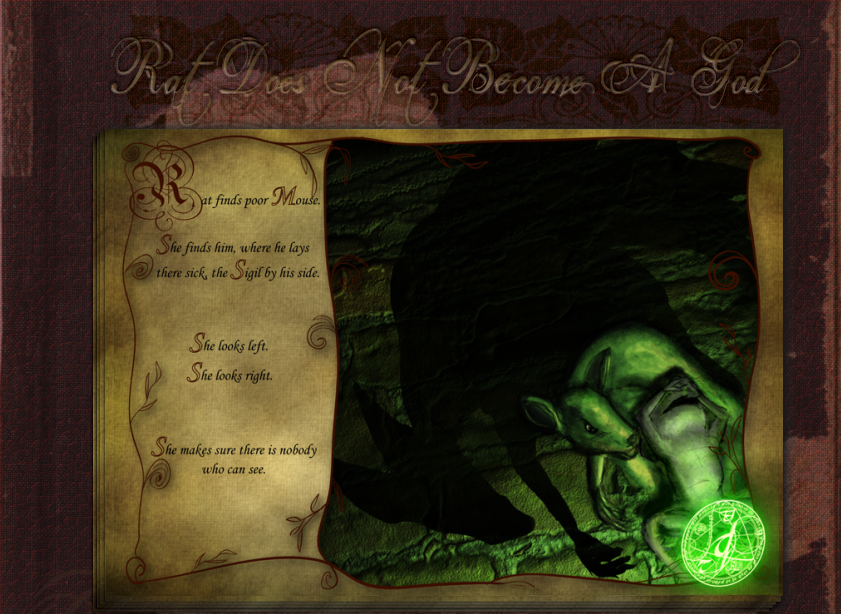

One creature has avoided it. One creature has slipped the serpent’s sight. It has hidden itself in the stirring silt of the ocean floor. It is not a sentient creature, not really. It has no brain to be sentient with, not really. It is an anglerfish. Yet, touched by the folding-wroth of the serpent, it has acquired a certain animus of destiny. It has become a potential ancestor of a sentient fish, of the Angler of Men, and some element of anti-temporal causality afflicts it with a touch of awareness in the now.

Because it could become something that knows the world of the future, it knows the world of the now. Because it could stand in the line of a timeless creature, it is infected with some elements of that timelessness now.

It feels things that it has never felt before. It becomes aware that it is hidden from the serpent. It becomes aware that it is not joining into the folding-wroth but is rather possessed by a certain angling-wroth, or possibly by that destiny-wroth that afflicts all things that believe, rightly or wrongly, that they shall one day be a part of something great.

It becomes aware that it has purpose.

It becomes aware of a path that opens before it, all full of food and life and destiny, until its genes pass on and escape it and it becomes of no further interest to its future spawn.

Then that future shutters.

The mind of the Angler of Men is defeated; it goes blank; its potentiality, as it has done before, and will do again before time’s ending, fades away.

There is a gun in Cheryl’s hands.

The gun is a hollow metal frame. It is a home construction. It shows clear marks of having been made in a student’s lab. However, as she releases the safety, this crudeness becomes inconsequential. A spark of brilliance, brighter than the sun, has formed within the metal. Lights that no one can possibly see run along the length of the gun, faster and faster, unless you happen to be a tree-falling-in-the-forest-sound-denialist, in which case, of course, there are no such lights at all.

The gun whines, high-pitched and strident.

Cheryl sights the serpent through the waters.

Cheryl pulls the trigger.

She parts the waters. She sears the deeps. The cod immolate. The eels immolate. The anglerfish and its destiny depart.

But the gun does not kill the serpent. It is hurt but it does not die; then it weaves itself through itself, reverses itself this way and that, and with each pass, with each awful breath, it is refolding, and the awful wound is healing, until even the scar of it is gone.

She fires again and again, she tries to outrace it — the serpent’s healing — but this does her no good.

It eddies away from her. It is gone.

– 6 –

“Would you like to be protected from bad weather at sea?” says Peter, because he’s aces at protecting people from bad weather, when they’re at sea.

. . .

“Actually,” Sally admits, “that would be kind.”

. . .

“Well,” says Peter, “done, then.”

Sally grins. She gives a little fist-pump. Then her attention drifts to Bethany. She gives a kind of sad half-smile.

“Bugs,” says Bethany.

“Eh?” Sally says.

“That’s my blessing. I can protect you from buggy software. Like, when somebody releases a new tape or cartridge for a marvelous computing device, it’ll usually have some sort of logic error buried deep in the code. But not if I’ve blessed you it won’t!”

“I . . . don’t need that,” Sally says.

Linus’ hand is on Sally’s shoulder. It tightens.

“That’s what you say,” Bethany says. “Then, one day, bam! And you’re wishing, if only I’d listened to Bethany back then and got her blessing!”

“You paint a distressing picture,” Sally admits.

“It’s all right,” Bethany says. She looks away, then back. “I actually protected you against software bugs back when you started staring at us. I thought, what if I die? So I extended it then, lest I feel ashamed in Heaven.”

Sally is quiet for a while. Then, softly, she says, “I’m sorry I broke into your room and tried to strangle and eat you.”

Bethany waves the apology off.

“It was wrong of me,” Sally says. “Us. I mean, we oughtn’t have attacked you like that. You wouldn’t have gotten that hat on. I thought it was good, but —”

“But sometimes,” Bethany says, “when you try to kill and eat people, they get hurt?”

“Yeah,” Sally says. She nods a couple of times. “Yeah, like that.”

She squints at Bethany. She looks at Bethany’s half-hand. She licks her lips.

“Well,” says Bethany, “I won’t say that it’s all right, but it’s all right. Are — is this another fight, then, or just apologies?”

Peter looks up at Linus’ eyes and looks away.

“You’re all really stuck,” says Sally. It’s almost a whine. “You’re so stuck. It would make so much sense to kill and free you.”

“Come on,” Linus says. He starts to pull her away.

“I was a jerk,” Peter says.

It’s reluctant. It’s like it’s being forced out of him. And Linus snarls. Linus turns. Linus presses Peter back into the back of the under-stairs nook with one hand and his teeth are bared and he says, “Don’t.”

“I shouldn’t have said,” Peter says.

“Don’t,” Linus snaps.

Peter closes his mouth.

“Don’t,” Linus, who will be Mr. Enemy one day, whispers. He lowers his hand. He looks down. “The more we eat, the hungrier we get. Did you know that? It’s so. And I think it must be that way with murder. The more we kill, the easier we kill. Kill you, Peter, and the next killing’s easier, and the next, and the next, and pretty soon I’m slaughtering kittens for canapés and murdering down the halls and the Devil won’t even bother putting on my skin because I’ll be wickeder than he. But I don’t know. I don’t know if I shouldn’t just do it anyway. So shut up.

“Because: you poor trapped creature.”

Peter doesn’t say anything. It’s not appropriate to say anything. Anything he could say would hurt Linus. So, against his own desire to speak, he doesn’t say anything. Linus shudders.

It is coalescing to clarity in Peter’s mind. The thoughts that circle the core of him like jaguars around this world of ours are spiraling inwards towards a sense-making.

He realizes that all he must do to reassure Linus here is to say something — say something normal, something imperfect, something that is not what a saint would say. Say something dumb, that he’ll regret later. Say something that’s what Peter would say, but not what a perfected Peter would say — not what Saint Peter, who is all that is right and good in him, would say.

There is something in the white hats that longs to free people from their chains; that will kill them, if it must, to set them free; this is both a preference and a hunger; so to comfort Linus he must simply say something unfettered, unburdened, something unaltered by his own red hat.

It’s very easy. It’s just like trying to mix yellow paint and blue paint to get green; only, instead of having yellow and blue paint, the only color that Peter has is red.

He can’t relax and be natural.

Relaxing and being natural is the right thing to do. Doing the right thing to do will only hurt Linus more.

His thoughts spiral faster and faster. Peter’s right eye pinkens.

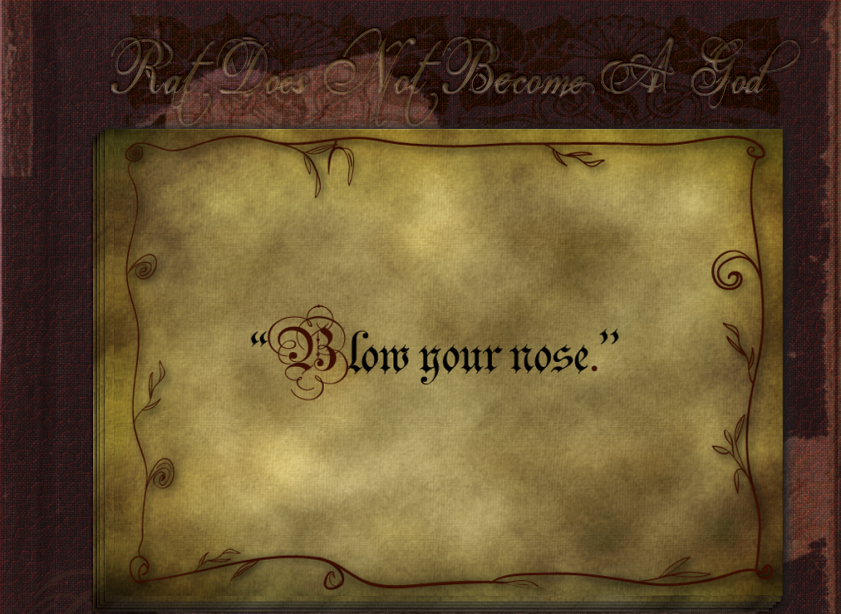

Peter’s nose begins to bleed.

“Good grief,” says Lucy.

She shoves Linus. He snarls, strikes at her, and misses.

“Just eat him or get out of here, you blockhead,” Lucy says. “People are going to think you two are a couple if you stand there stammering at one another much longer.”

Linus makes sputtering noises. Peter rubs his nose.

“Well,” says Peter, because it’s the right thing to say under the circumstances, “I hear that when you hang out with the Devil, that’s like hanging out with everyone who’s ever hung out with the Devil —”

“Oh, God,” Linus says, and skitters away to make fake retching and gagging noises with his tongue on fire.

Sally, after a moment, goes to help, although neither of these things are actually activities with which she can assist.

They depart.

Lucy, though, she stays behind. She stares at them for a while.

Bethany opens her mouth to say something. Just before she does, Lucy speaks.

“You’re not good for us.”

“I know,” Bethany says.

“I don’t know what that boy’s got in his head,” she says, meaning Edmund, “but I’d rather not eat more people than I can afford to. Each person I eat, that’s got me that much closer to the wolf. That much more under his power. I can’t afford that. I don’t want this wolf-power. I want my own.”

“You’re not very good for us, either,” Bethany points out.

Lucy hesitates. She looks confused.

“I mean, with the eating.”

“Oh,” Lucy says. She waves a hand dismissively. “You’ll get over that, when you’ve been eaten.”

“That’s an extremely problematic position!”

“Yes,” says Lucy. “I’m an evil prophet.”

Bethany tilts her head. Then she smiles gently.

“Well,” she says, “An evil prophet that won’t suffer from softwa—”

Lucy almost rips her eyes out. Bethany ducks. Lucy follows up. Her knee comes up. Bethany is spiraling off through ninja-space; but there, outside the world, she sees Lucy’s hand, larger than world or void, come closing in. She staggers down to fall against the remnants of a Michelangelo with Lucy’s hand around her throat.

“No,” growls Lucy. “No blessings. I don’t want your hope. I don’t want your dreams. I will get bloody gout if I want to get bloody gout. You are a filthy planetary people and I will have none of it. None of it. Do you understand me?”

Bethany blinks.

Her backup gun — it was hidden in the wall, under the Michelangelo — is in her hand. It fires full-bore holy bullets into the gut of the evil prophet of —

No.

That doesn’t happen. Lucy sees it coming. She explodes into a vaporous white pall that scatters through the hallway, just in time to realize that Bethany cannot possibly have a backup gun hidden in the wall behind the Michelangelo just waiting for Linus to eat his way down to it and then for Lucy to hold Bethany pinned there.

She re-condenses. She starts to shake her fist for rock-paper-scissors.

Bethany is moving forward, a shining lance of sacred steel in her hand —

Lucy shutters closed her third eye. She blinds herself to the future. She attempts to press the attack, but somehow this fails too; she is sprawled indecorously on the floor.

Bethany sits down beside her.

“Damn it,” whispers Lucy.

“I’m sorry,” Bethany says. She brushes aside Lucy’s hair.

“Your filthy world.”

Lucy pulls herself up. She looks at Bethany. Then she sighs.

“It’s not really your fault,” she says. “I guess. You’re just . . . doing that thing. That saint thing.”

“No,” says Bethany.

“No?”

“I’m not really doing that saint thing,” says Bethany. “I’m just going through the motions. There isn’t actually any hope for me, any longer, so I’m just sort of living.”

“Oh,” says Lucy.

She smiles a little.

“That’s great,” she says. “That’s awesome. Thank you.”

Bethany looks perplexed, since she’d expected either sneering or sympathy. She’s even more confused when Lucy hugs her, not with comfort but with cheerfulness, and then doesn’t try to kill or eat her even a little bit!

“Um,” says Bethany.

“That’s what I want,” says Lucy. “That’s all I want. All I want is for everyone on your world to give up hopes and dreams and hungers and succumb to the will of the wicked god of space, and then to die when the Fan Hoeng space fleet arrives. I didn’t know. I’m so, so sorry. I wouldn’t have tried to eat you if I’d known.”

She pats Bethany on the shoulder. She walks away. She is whistling.

“Why do cannibals keep apologizing to me?” Bethany asks of Heaven, but Heaven has no real answers for the House of Saints.

– 7 –

Tom works on a trap-line to make sure the nithrid doesn’t destroy his building. He mutters to himself. He looks up.

Emily is smiling at him.

He’s reminding her of her godfather Eldri, and of happy summers, and of how glad she was, just recently, to hear he’d gotten out of the hospital and that the cancers that had bloomed in him after the nuking of Bibury appeared to finally be gone.

He doesn’t know that, though.

To Tom, it’s just all summery sweetness. He looks at her and he sees what he imagines must be a fellow Dreamer.

“I have a hat,” he says.

He takes it off. He holds it out to her.

“I couldn’t,” she protests.

He tries again. “I mean,” he says. “It will refine you. It will awaken you. It will make all that flows through you, and is in disorder, into a single stream, and pure.”

She looks at it.

She shrugs. She tries on the hat.

She licks her lips. She doesn’t say anything. Her eyes film for a moment, then come up streaked with yellow gold.

“I . . . really need to stop giving my hat to random people,” confesses Tom.