– 10 –

Bethany duels Edmund in the sky above the school.

Why?

Well, it’s only natural.

I mean, specifically, it’s only natural that in a whole school full of renegades and bad elements, there’d be one or two people who’d object to having cannibalistic wolf-people running around eating other students and wearing non-regulation hats.

Such as: Bethany!

Also there was Theodore Cetera, but he had already been et.

Bethany slams Edmund down. She stomps him into the ground. She stops just short of killing him, though. She takes his hat and leaves him to grovel about on the earth, instead, desperately whining for someone, anyone, to bring him a new white hat to wear.

She should have killed him, of course. Humiliating him was pointless. But there’s something about killing fifteen-year-old kids that makes it hard to feel morally at your best.

Even if you’re only sixteen and a half yourself!

That night, she realizes her error. She realizes her error because she wakes up and Sally is in bed with her. Only, Sally isn’t planning to do something naughty with her. Sally is planning to kill and eat her.

. . .

Possibly I have phrased that poorly. I mean, Sally is not planning to do something untoward.

The point is, I mean —

Spudgeflidgeon.

What I mean is, this story is going to retain its solid for-young-people rating. It is not going to have two girls in bed together doing something of which good upstanding Christian adults would not approve. Particularly when they are really young and immature. So instead Sally just attempts to strangle Bethany.

Bethany isn’t quite awake yet. She has vague dreams of a slavering maw and a pale, stretched-out face. She flinches, reflexively. She throws Sally into the wall above Bethany’s bed. This resolves the problem for all of two seconds before Sally falls back on top of her. Bethany slams her against the other wall over her bed and this time manages to twist her enough that Sally falls onto the floor instead of back on top of Bethany, and with a ringing clang.

Bethany curls up in her quilt. She tries to go back to sleep. Sally lunges up from the ground.

Bethany bonks her on the head.

Sally goes down. Sally clangs. Sally shakes her head vigorously. Sally tries to stand up again.

Bethany flails. She is not actually trying to knock Sally out. She is trying to press Sally’s snooze button. But the Sally-beast has no snooze button! Sally bites off two fingers of Bethany’s hand.

“Gah!” says Bethany.

She wakes up. She spurts blood in Sally’s face. She draws her night-tanto, which is like a regular tanto only it is smaller and snugglier for sleeping with. Its sheath is basically a teddy bear, only long and solid and straight. She squirms into a crouch.

“Get out, Sally!”

Sally is her neighbor. Sally was her neighbor. Now Sally is a member of the House of Hunger who has broken into her room, tried to strangle her, and eaten two of her fingers. This does not affect her residential status but it is arguably not neighborly.

Sally lunges. Bethany stabs her eye. It’s grotesque. Sally claws at her.

Bethany pulls back. She crawls to the far end of the bed. She stabs Sally again. Sally bites through the blade.

“Get out!”

Bethany tries to remember what a proper ninja does in this situation. It is difficult because she is wearing fuzzy pajamas. Well, it is difficult because she is wearing fuzzy pajamas that are not black. They have an adorable frogs and fishes pattern instead. Then she remembers, just as Sally scrambles up onto the bed with her again.

Bethany twists sideways and vanishes. She transcends reality. She walks three steps through the shadow world. It is exhausting and she cannot breathe there. She tumbles back into reality outside the walls of her dormitory.

She catches herself —

Well, first, she falls, but then she catches herself — against a window railing two floors down.

Sally leans over the open window. Then Sally begins to crawl down the wall like some vast gecko.

Edmund’s leaning, kind of casually, against a tree not far below.

“Damn it,” Bethany says.

She lets go of the wall. She drops.

“Don’t start fights,” says Edmund, “that you don’t intend to finish.”

He makes a head-gesture. The Bernard-beast approaches, and the Lucy-beast.

“I didn’t —”

Bethany remembers that technically she had started the fight. She had stopped Edmund from eating Sid, who had really seemed to have enough problems on his plate already.

“Well, fine,” she says.

Then she is a river of motion. Then she is striking this way, this way, and that. The sharp point of her wrist catches the Bernard-beast’s throat; he gags, chokes, and goes down. She hops on one foot, backing away from the snarling Lucy-beast’s attack, long enough to rip out the emergency footie-knife from the footie of her pajamas. Then she takes the offensive, but Lucy slides back and away. She is as elusive as the wind.

Then it seems like Bethany has her. Lucy’s eyes are wide and cavernous; they draw Bethany’s attention in, they fixate her, and she slams the knife towards Lucy and Lucy does not dodge —

Edmund catches Bethany’s hair. He pulls her staggering back.

Sally has caught up to them. She springs snarling for Bethany’s leg. Bethany topples. Bernard is recovering. He is pulling out his own weapons now, glass wind-and-fire wheels — like fist knives, only with razored glass semi-circles for their blades — and Bethany’s knife has gone skittering away.

She’s almost out of night-time backup weapons. There’s the wire in her hair, of course, and the suicide tooth, but she doesn’t really want to spit the suicide tooth at anybody and it’s really hard to get the wire back in once she’s ripped it out.

She’s first-ranked in her class. She is on track, as she tells her friends when lazily hanging about on the couches in the dormitory lounge, to be the Valedictorian of Lethality, or possibly of Lethal Magnetism, at the end of the following year.

She is Bethany.

Edmund discovers that he might not want to be holding on to Bethany’s hair. She twists about him, tangles about him, dances as even the nithrid dared not dance, and a confused Sally gets a mouthful not of Bethany but of wolf-gold and Edmund’s back.

Edmund can’t help it.

He snarls. He lashes out at Sally. The hunger in him escalates into an ulfserk fury and Bethany is skipping away, fluttering up into the trees, her eyes a gleaming in the dark.

Lucy is waiting for her.

. . .

Bethany practically backs into her. It’s only the utter silence where Lucy is, the unswaying of the branch she stands on, that gives the Lucy-beast away.

Bethany elbows at her, hard. Lucy dodges but staggers. Bethany squints.

“That’s right,” she says, recognizing the girl under her hat. “You’re on the prophesy track, aren’t you?”

Lucy snorts. She tosses her head. “I,” she says, “am the evil prophet of —”

She doesn’t get to finish. Bethany moves in such a fashion that if Lucy finishes that sentence, she will fall and break her neck.

Lucy snarls. She opens her mouth. She tries to start again.

She will introduce herself. Then she will speak an evil prophecy. Then there will be only blood and death for Bethany, as she will have foretold —

Bethany is looking at her. Bethany is intending at her.

Lucy howls.

She gulps back the evil prophecy. It roils in her wolf-gut. That path leads to disaster. What about . . .

Bethany moves, just a little.

Lucy, tangled up in prophecy and forebodings, throws herself from the tree and hits her own head hard on a wayward branch.

. . .

Bethany ducks under Bernard’s blades.

The Bernard-beast is vicious. He is also quite well-dressed. She finds herself admiring the cut of his garment as he swings invisible blades over her head.

She ducks, planning to catch those blades in the trunk of the tree she’s standing on. His blades scissor straight through the wood, instead, in a great spray of chips and bark.

“Jesus,” swears Bethany. Later, if she survives this, she will add a shilling to her Jesus jar. It’s a swear jar, shaped like Jesus. But that’s not important right now!

Sally has lost the accidental struggle. She has curled up, whining, licking her wounds (except the missing eye) beneath a tree.

Edmund is coming for Bethany.

Bernard punches as if to stab through both Bethany and several feet of wood.

Bethany falls sideways. She twists in the air. She transcends reality. She jogs a few steps downwards, reappears delicately poised one-footed on Edmund’s head, and heel-kicks his nose hard with the other.

Then she twists sideways again as Bernard descends —

Bernard follows her into non-space. His glass weapon here gleams a brutal gold. It cuts her. It tears her side open. She gapes at him and bleeds as he falls back into the world; and has only a second or so to stagger in a random direction away from him before reappearing herself.

He has guessed her place of emergence almost exactly. She loses a lock of hair. That pushes her to the decision point.

She rips the wire from her hair.

He comes at her again. She locks eyes with him. She shoves his consciousness out of the way for a second so he doesn’t cut her again, comes in at him, and wraps the wire around his neck. She pulls —

Lucy seethes up from the ground in a cloud of air and darkness. She hauls around a gunbrella to point at Bethany. It beeps, charging. Bethany can’t intend at her with two hands full of garroting the snazzily fashionable Bernard!

Edmund is getting up.

Bethany tightens the wire. Bernard’s throat begins to bleed. He thrashes —

She still can’t kill another student. She rips his hat off instead. It doesn’t come off. He’s glued it on.

“Gah!” she howls, incoherently, beats his head against the ground twice, and runs.

There is no specific jar for incoherent howls. It is a good mental practice for her to sort through such things later and figure out what swear she would have used, had she had the proper mental presence for obscenity.

She breaks Edmund’s knee fifty yards later, by which time she has a stitch in her side and Lucy’s gun is fully charged.

She drops to the ground as it fires. Lucy fires at the ground. Bethany twists desperately away from reality but she still winds up seared and aching.

She jukes the followup blast onto her shadow. She staggers up against a wall.

She is dirty, beaten, and battered.

She looks up. She looks around her. She scans for hope. There’s a gun emplacement in the bell tower, but — it’s unlikely to have tranquilizing weaponry.

This is a Lethal School.

She sights Tom Friedman, science adventurer.

. . .

Tom is sitting alone on a bench. He is admiring a stand of mutant pipe cactus. The blooms have opened in the night and are releasing a rich and alien scent.

She turns sideways. She appears sitting beside him on the bench. He startles three feet rightwards.

“I need it,” she says.

“What?”

“I need it,” she grits out. “The hat. I can’t kill them. I can’t keep fighting. I can’t breathe.”

He looks her up and down.

“You’d just wind up joining them,” he says, dismissively.

Edmund verges onto the scene. Bethany kicks a cobblestone from the ground into her hand, throws it, beans him.

“Not mad scientist material?” she asks.

“The correct term is ‘innovator,’” says Tom peevishly. “Or merely ‘scientist.’ And no.”

“All right,” she says.

She stands up.

She looks down. She looks up. She takes a breath.

“You’ll have to watch me die,” she says, “then.”

“Actually,” says Tom, “I can just go home —”

“You are a complete and total jerkface,” she says.

He ponders this.

It is, as it happens, not true.

“Fine,” he says.

He tosses her his hat. She puts it on.

. . .

Thus is she sorted to the House in red, the House of hope, which is named also the House of Saints.

– 11 –

Lightning thrashes the grounds of the Lethal Magnet School for Wayward Youth. A wise child would not stay out in it, but would retreat to bed — or better, to a cave — to wait it out instead.

Bethany isn’t a wise child. Nor yet are the enemies who come.

She tosses Tom’s hat back to him. He snatches it. He retreats.

“Red,” Bethany whispers. “I must wear red.”

Lucy and Edmund circle around her. The other two have fallen a bit behind.

Bethany is distracted by a flash of lightning. In that moment, when her eyes are drinking in the nithrid’s radiance, Lucy seethes at her as an evil mist of aerated prophet. There is no time to dodge, at least not properly; nor could she dodge, not with such dazzled eyes as these.

Bethany vanishes, instead, in a swirl of red; it is like a fountain of rose petals and carmine smoke bursting upwards from the ground where she had been.

Lucy condenses; Lucy, who has wickedly counted out three counts while dissipated into prophet foam with neither visible hands nor arms to count with, throws paper.

Bethany is not there.

Bethany has gone to ninja-space, and beyond ninja-space, to Hans’ wardrobe deep under the surfaces of things.

She falls back into the mortal world clutching a hat that has no equal in all the world.

It is that hat which reminds us: if we do our best, if we are good and strong and determined, then everything will end OK. No matter what. We are enough. It’ll end OK.

It is a miracle hat. It is a hope hat.

But more importantly, it is red.

She puts it on.

“Now then,” she says.

Edmund moves at her, but she is gentle with him. She pushes him lightly to the side; he goes past her, stumbling. Lucy has stopped moving; Bethany is confusing her prophesying, and hence her very sense of reality, with careful thoughts.

She grins at them.

“I am one thing,” she says. “Now, where I was many things before. Do you really think you can kill me?”

She turns. She disdains them. She disrespects them. She walks, with her back to them, towards her dorm — only, an evil feeling strikes!

She dodges. She tries to dodge. She fails. Edmund hammers her into the ground.

“I am not,” he says, “that easy, you filthy splot.”

He’s right. He isn’t.

He was that easy, but he isn’t now.

He doesn’t let her get away just with transcending mortality. He doesn’t let that be enough. He draws full upon the strength of Fenris Wolf and he is mighty.

It surges in him.

It burns through him.

He is strong as beasts are strong and fierce as a world-devouring wolf.

In the face of her sainthood and her red, red hat, his stomach growls and he steps up his game; his pupils are devoured by an awful white.

He slams her back. She is having trouble dodging him now; there is a fatal element to his punches, each has the weight of destiny to them, she finds herself in a world where the previously vast probability that she would dodge each one dwindles directly to almost nil.

He eats the chance-lines where she escapes him.

He hammers her back, back, back, he shoves her up against the wall and his teeth are bared and he says, “Shall I free you from your chains?”

She kicks. She fails.

“You’re not going to say it, are you?” he asks. “You’re not going to tell me what Peter told me. You’re not going to tell me I’m not to eat you. Because I am, aren’t I? I can eat you, can’t I? Hahahaha, I can!”

She dissolves into flower petals and mist but he shoves his hand through her dissolving form and grasps her shoulder muscle and she hisses and screams and she falls back to flesh.

She sags.

“If you can beat me, you get to kill me,” she admits. “That’s my samurai code! But I’m not done yet.”

“Be done,” pleads Edmund. “Let me free you.”

“No way,” she says.

She knees the air in front of his groin. (His actual groin is out of reach.) If you were a man, and also made out of air, you would probably wince in sympathy. But Edmund doesn’t even move!

She isn’t actually a samurai at all.

“Let me free you,” he says. “You are trapped into a hideous existence. I will cut you loose. Then I will eat you. That will be my payment. It is a small reward. I only ask the flesh.”

She doesn’t understand for a moment what has happened.

She doesn’t understand why he won’t just get on with it, where his confidence and power went, until —

“Oh, dear,” she realizes. “The slavering wolf-boy doesn’t want to murder me.”

He pulls his hand out of her shoulder. The sound is awful. She goes absolutely white. He licks it off.

He looks away, sulkily.

“It’s important for someone to agree with your reasons for killing and eating them,” he says. “That’s democracy.”

It bursts out of her as laughter: “What?”

A flash of fury from him. He rips off her hat.

It staggers her. It makes her mind all chaos and disorder because it is the nature of a Bethany to wear a hat of red.

“You’re in such an awful trap,” he says. “You see.”

She is completely distracted. “Give it back,” she says.

He squints at her.

She sinks down to the ground. She is begging. “Please. Give it to me. Give me back my hat. There is only one. That is the only one in all of unbeing beyond time and space.”

“I will trade it,” he says.

She shakes her head. A dead girl cannot wear a hat.

She reaches for it.

He holds it back.

“Don’t you want —” Her brain is in confusion. She scrubs her hands raw and red on the pebbles. She holds them over her hair. She can’t think. “You don’t want to do this. You want to give me your hat. Don’t you?”

Bloody hands are not a red hat. She tries but it’s not good enough. Maybe a little rock —

“You want to give me the hat,” she says, “because it’s right. It’s right and proper and important. Please.”

He’s turned away from her. He’s walking away. He has her hat.

He doesn’t understand. He can’t possibly understand. How can he understand what he is doing? He must just be mistaken.

“It’s the one in your hands,” she explains.

He’s gnawing on the edge of it.

“Please.”

Eating her hat is a bad thing to do. Probably. That is what Edmund suspects. It is probably a thing that only a bad dog would do. It is like killing people, only maybe it is better or worse. He isn’t sure. He probably should not. Didn’t she say there was only one of them?

He is so very hungry.

Maybe Sally will eat the girl, and then he can eat Sally to remind her that one should always get permission from people before killing and eating them. That would be a good and moral action. That would be the right thing to do.

“Why do you make me think about things like this?” he says, angrily.

He is staring at her.

She is staring at him. Her face has gone completely bleak and lost. He realizes after a moment that he has accidentally eaten the whole hat.

He licks a bit of felt from his lip.

“Sorry,” he mutters. He looks at her arms.

“My hat,” she says.

“Your arms,” he says. She looks at him blankly. She won’t miss an arm, will she? Hats, he thinks, are not very filling at all.

It’ll help him break Fenris’ chain.

She shouldn’t be so obstinate! It is just one arm. And maybe another arm.

She is crawling away. He should stop her. He should eat her. He shouldn’t eat her —

“God damn it, Lucy,” he says, because the evil prophet of space is about to kill and eat Bethany by murder; and he cuffs her and they fight and snarl for a bit, and then somehow they get into a rock-paper-scissors match and she creams him five times in a row even though he is head boy of the House of Hunger and she is just a space princess assassin who always throws paper, and he bites great chunks out of stone cherubim only to discover them practically indigestible and he staggers grumpily away.

He is so very hungry. He is so very bad at cannibalism. This night has gone so very wrongly.

Bethany so very badly needs a hat.

Entities Frozen under the Ice

It’s lucky that they’d invented the satellite that sees around corners or they’d never have gotten Special Topics in Entities Frozen Under the Ice going. Before that, the entities frozen under the ice were purely hypothetical; notional; legends. Fragments of a history predating the world.

Now, of course,can look at them. Study them. Analyze them, on behalf of the Lethal Corporation, to prepare both corporate and students for whatever the satellite finds.

That’s how Moah discovered the chimerae.

All the things that Hans buried.

The princes. The witches. The frogs.

And the thing, of course, that means that nobody can know. Nobody can be allowed to know. Ever.

If people knew, they would find it. If people knew, they would free it.

The satellite photos get roundfiled. The photos of those — you can obviously get a good look at Professor Moah’s desk if you’re a satellite that can see around corners — those get roundfiled too.

Only vague descriptions escape.

If people knew what was found, they would not rest until they had seen it for themselves. Having seen it, there would be no help for it: they would save it.

If people knew, they would save it, and disco would return to the world.

Chapter 3: The House that is Silent

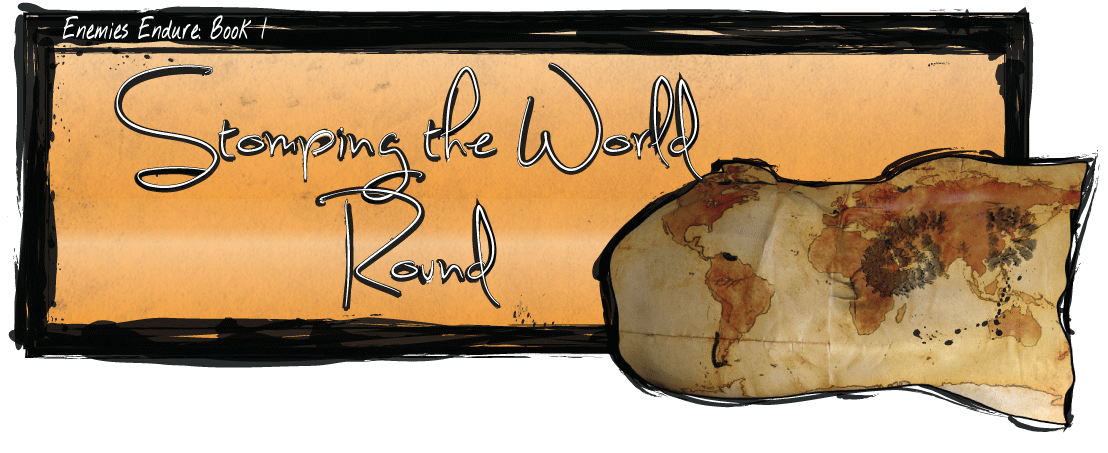

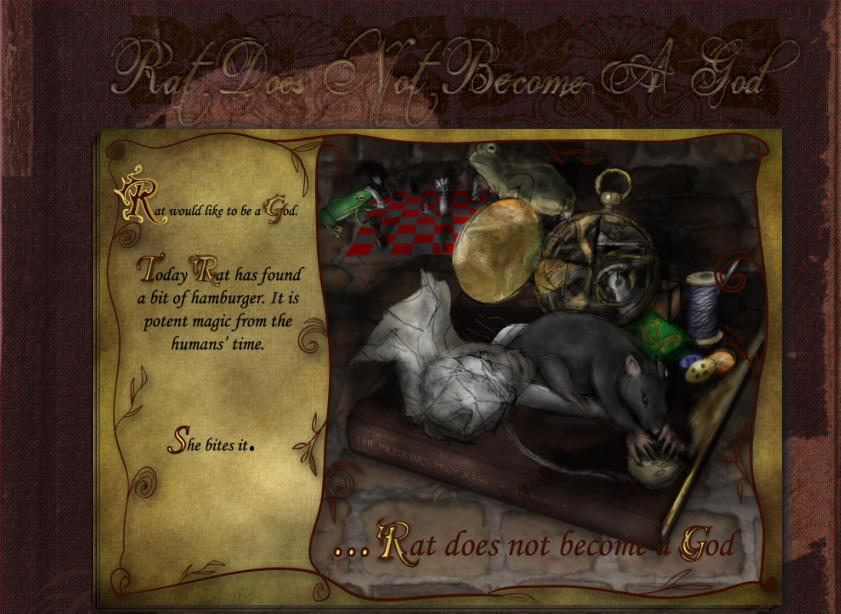

- . . . Hans, it was, who dreamt of such an ending. Hans, who stomped the flat world round. Hans who climbed the sacred mountain; who spoke forbidden words upon it; who brought dread winter down upon the world. . . .

(illustration by Anthony Damiani)

– 1 –

The nithrid rages across England. It flares up and it flashes down. It howls across the sky, devouring other storms. For a while, the world ignores it; but —

It has begun to kill.

Just here and there. Just a trickle. But it has begun to play in this brand new world that Edmund has given to it. It has experimented with flashing down into a city, lighting up the buildings, making them dance St. Vitus’ Dance, and chasing and slaughtering the men and women on the streets. It swirls up and down and all about in great gusts of lightning and —

It passes through the School. It’s a mix of nostalgia and vague stress; being a living storm, it has no way to turn in its last few homework assignments, or attend to its midterms, and somehow it has gotten the impression —

I really can’t imagine from where —

That its secondary school grades and record will be of some sort of account.

It doesn’t understand what a nithrid should understand, to live in a world like hers, which is: the world belongs to anybody who can power entire cities, live a long time without consuming financially costly resources, and write programs for the marvelous electronic computers so prolific in that futuristic age.

There’s really no need for her to have high marks!

Yet there it is, sweeping back through the School now. I just don’t know what it’s thinking.

Emily lugs a PlayStation 6 up onto the roof.

The nithrid ignores her. It doesn’t recognize its danger. It thinks, at most, that she’s out there to see it; that she’s appreciating the lightning; it doesn’t mind, and it doesn’t kill.

Emily goes back down. She lugs back up an uninterruptible power supply.

She plugs the PlayStation in.

A light burns gold.

The sky groans.

The nithrid writhes, and the lightning stops. The rain becomes a perfectly, precisely steady flow.

After a while a single arc of lightning comes down. It is struggling, as if pushing through molasses. It progresses slowly. It touches down on the roof facing Emily. It skitters there, still and steady, holding itself against the ground.

It is like it is staring at her.

Nithrid.

“This is how it is,” says Emily. “This is the Konami Thunder Dance. The sun won’t move. The rain won’t start or stop. And there’s not going to be any more of that lightning, nithrid. Not until I start the dance.”

The nithrid eddies.

Emily brushes back her hair.

“I hear tell,” she says, “that a living storm’s been making havoc over the British Isles; and growing too. That that savage beauty, called a nithrid, has come back to make an end to cities and to civilizations and to all the works of humanity.”

The lightning traces across the roof. It makes a symbol. She looks at it.

“I don’t . . . read . . . Sumerian?” she says.

It scribbles the symbol out. It tries again in letters writ much larger: YES.

“I see,” she says.

There is a bit of silence.

“The world Konami Thunder Dance association tells me that I’ve got first crack at this,” she says. “Since I’m here, and I’m the best. If I fail, though, there’s others to come after me. Max. Meredith. Even Lucy. And plenty others after those. So, I’m going to dance against you, and I’m going to win, and you’re going to quit it. Not because you agree to. Not because you’ll choose to. Because this is the revolutionary PlayStation 6 dance pad game that is going to tear you apart.”

Lightning is writing on the roof.

It is writing largely, looping: TRY ME.

She presses the power button with her toe.

There’s no turning back now.

Only, there is.

She is with it and within it. She is wound through it and it through her; she is dancing amidst the lightning, and she is binding it up again; it is as if her spirit has flown up from her body in the shape of a bird, as if it weaves in and out among the branches of the storm, among its stations, and where she goes it follows her, and she is threading it into knots. Each step she traps it tighter, she twists it about itself, and whether it strikes at her or dances with her, it only pulls itself more stringently into the shape of the tightening knot.

In this dance, she will be victorious, but —

There is, in fact, a turning back.

She kicks off the game.

There is a sudden silence. The lightning tears itself out of the knots she’s woven into it. The storm howls. It flares. It strikes before her, white, incandescent, searing the air in front of her face and damaging one corner of the coating on her KTD pad.

It draws back. The nithrid scribbles over its previous messages.

I DON’T NEED YOUR PITY

She just turns, though. She walks away from it.

I WILL KILL THEM. MEN. WOMEN. CHILDREN. I WILL KILL TH—

It stops writing. She isn’t looking. She’s walking down the fire escape.

She says, “Then start with me.”

It does.

There is lightning all through her. She stumbles. But it does not kill her. After a while she is conscious; she glares down at a fresh new scar.

She staggers away, limping.

The storm departs.

“God damn it, Emily,” says Max, later.

She looks at him.

“You taught it to stay away from the Thunder Dance. Why didn’t you finish the bloody thing?”

“I decided that I shouldn’t,” Emily explains.

– 2 –

Saul performs. He rocks. He peels his music from the heart of him before the screaming crowd, and sweat rolls off of him in streams.

It’s helpful, really.

It helps his glass harmonica play.

There’s friends on the guitar and drums behind him. There’s rebellious globed lightning that reacts to the music, too; for what’s rock for, if not to laugh in the face of the Devil, the nithrid, and all their ilk?

But mostly there’s just him, and his seven-foot glass harmonica, and his body, drenched with sweat.

He’s forgotten he was a svart-elf. That’s his reincarnation!

Now all he can think about is his rock and roll.

It’s not as simple as that, of course. It’s not as simple as “wake up human one morning, and also a baby, and eventually go into performing arts.” There’s lots of stuff in between!

It’s just that —

All his life, Saul’s been told he was bad, and he knew it was wrong, on some level he knew it was wrong, but he’d honestly forgotten that he was good. He’d forgotten about the sugar fairies. He’d forgotten about the Land of Pleasure and Happiness and the fact that he could have gone there. He’d forgotten about everything, really, right down to the puppy that had called him back.

So after a while, he just started accepting he was wayward.

He bent himself and hammered himself into the mold of somebody wrong. Drugs — though, and he’d never admit this to anybody, he mostly takes placebos. Loose sex, principally alone. He kisses budgies, lavishly, and without precautions. And of course there is his . . . Lethal . . . rock and roll.

His music is the kind that can sink its teeth into the human heart. There’s no one at school save Edmund who can really ignore it. Saul was good when he was born, he was a melodious baby, and he’s better now that he’s grown; and a little bit of the smith-wroth’s still in him, so he’s best of all with the tools he’s made himself.

It takes a svart-elf to make a band out of guitar, drums, globes, and glass harmonica, but Saul, he makes it work.

His concert ends with a crash. He smashes a carefully prepped and separable section of his harmonica. It shatters on the stage and releases scent.

He takes a towel. He wanders backstage. He mops himself off.

He catches a bottle of brandy someone throws at him. He mimes drinking it down. Later he drops it in the liquor recycling bin (the school has separate recycling bins for glass, paper, plastic, and unused liquor) and collapses into his chair in the rooms backstage.

Tom shakes his hand enthusiastically.

“Rock,” says Tom. “You, sir, are a genius. Your music lives.”

“Huh?” Saul says.

He isn’t sure how Tom got backstage and into his room there. The answer, incidentally, is “Tom controls swarms of robot bees.”

“Oh,” says Tom. He smiles. “I came to honor you.”

He takes off his hat. He proffers it.

“It’s not underwear,” says Saul, pleased.

Hardly anyone gives rock stars their overwear. It’s a new experience.

“Yes!” agrees Saul, more with himself than with the narration, and he puts it on.

“Lo,” he says, standing up, striding, preparing to declaim something, “I am crowned Saul the —”

His voice shorts out. He staggers. He goes down on one knee.

“Oh, come on,” he says. He shakes his head vigorously. “No!”

He falls over. He kicks his feet.

“No. I won’t let a hat, I won’t, it won’t, a hat won’t beat me —”

Power rages through the channels of his brain. His eyes roll back. He screams.

They come back down gleaming red.

“Oh,” he says.

He makes a strange face at Tom. He takes off the hat. He hands it back to Tom. He improvises a red hat out of bits of torn uniforms and roses that are laying around the room.

He is crying.

“What?” says Tom. “What?”

“What have you done to me?” says Saul, like he wasn’t prepared for this, like at no point in all his life of rock and roll, drugs, and fevered debauchery has anyone ever warned him that he might actually be some kind of saint.

“What?” says Tom. “What?”

Saul points at him accusingly. “You’ll never get gout!” he tells Tom, which is true, but isn’t at all what he expected he would say.

“Thanks,” says Tom.

Then his face falls, slowly.

“Dang it,” he says. “I’d really thought you’d wind up in Dreams.”

“I can’t play music,” says Saul. “My drug habit. No more pirating torrents. What am I going to do with myself, Tom?”

“You’ll find something!” says Tom. “I’ve got faith in you!”

He claps Saul on the shoulder.

Then he grimaces, like he wants to join the saint in crying.

He turns.

He lowers his shoulders. His back is as expressionless as a . . . back. . . is as he trudges, quietly, away.

– 3 –

As for Bethany, she finds a hat.

It does not suffice.

Nothing suffices. She tries more and more elaborate hats, and simpler ones too; and different shades of red.

Finally, bleak, her face a pale ghost’s beneath her florid red bonnet, she stands upon the edge of a rooftop and she sways.

“I cannot make myself give up,” she says.

They have come, of course: the others in her House. Peter sits on the edge of the roof beside her. Saul, he sprawls.

“That would be unsaintly,” says Saul. “If nothing else.”

“It’s just,” says Bethany, “that for a moment, I thought, because I’d worked hard; because I did my best, and strove for right things, that I’d have a miracle come down to me, that I’d reach the happy ending. And then Edmund ate it.”

“That bastard,” says Saul. “How dare he eat somebody else’s happy ending?”

Bethany tries not to laugh.

“Bloody heck,” mutters Peter. “Now I’m hungry.”

She can feel them in their red hats behind her, and to the sides. She lets herself fall backwards onto the roof, instead of forward. She lands hard enough to crack the concrete, but it doesn’t seem to have affected her at all.

She stares upwards at the stars.

“A long time ago,” she decides, “I think, a wicked god of space came to Earth, and told us that there was no hope. That nothing meant anything. That nothing would ever mean anything. That we were just pathetic sacks of meat, trundling around about our lives. But people kept looking up at the sky anyway, dreaming and hungering and hoping, so it had to fly away.”

“That’s probably where the scissors came from,” Peter says.

“Oh?” Bethany says.

“Yeah. Some guy was just sitting at home trying to cut paper with a knife, and suddenly he thought, ‘you know, I bet there’s no hope. I bet I’m just a pathetic skin-sack full of meat. So I’ll stick one knife on this other knife, on a kind of hinge-like thing, and thus express my existential despair!’ Poor man! If he’d thought to add a third blade, you know, he would have seen that there are good things left in this mortal world.”

“No,” Bethany says.

“No?”

She reaches for the sky. She takes a handful of space. She looks at it. It doesn’t seem much different than any other handful of nothingness. She blows it away.

“It’s not about whether your n-issor has two or three blades on it,” says Bethany. “It’s all about the quality of your hat.”

They’re silent for a while.

“I don’t like being a saint,” says Saul.

“Oh?”

“I’m a druggie,” says Saul. “And I was a musician. I did Lethal rock and roll.”

“Oh, that’s who you are,” says Bethany. She beams. “Saul, right? I liked it. With the spinny table thing.”

“The . . . yes,” says Saul.

She gives him a thumbs-up.

“I don’t know who I am,” says Saul. “This isn’t who I was expecting. I mean, maybe it’s better? But it’s not right, it’s not like the me I was used to being at all.”

“Sometimes,” says Bethany, “we have someone inside us who we’re not expecting.”

“And then they surge out,” says Saul. “And take over!”

“No,” says Bethany. “That wasn’t where I was going.”

“Oh?”

“It was going to be more, you know, inspirational-like.”

“Oh,” says Saul.

He laughs.

“Is that what you do? Inspire? I mostly keep people from getting gout.”

“Seriously?”

“Yup!” says Saul. “I point at people. I bless them. ‘Gout, get out!’ And it skedaddles. Or ‘you won’t get gout!’ And they don’t.”

“I can protect people against buggy software,” says Bethany.

Saul whistles.

“I’m aces at protect—” Peter stops. “Sorry.”

“Hm?”

“I was interrupting. Buggy software. Go on!”

“That’s it,” Bethany says. “Like, bam, you are never going to be messed up by buggy software. I think I can also protect people against science in general but that seems a little rude.”

“I’ll pass,” agrees Saul.

There’s a bit of a lull. “At what, um . . . you?” Bethany asks, pointing at Peter.

“Oh,” Peter says. “Storms. At sea.”

“No, no, name first,” she says.

“Peter,” he says.

“Bethany,” she says. “I want one of those blessings.”

“Sure thing,” says Peter. “Bam! Protected.”

“Saul,” adds Saul.

“We’re like Pokemon,” giggles Bethany.

“Saul — saul?” says Saul. Then he frowns. “No, this is unfair. You two have much better names for Pokemon.”

“Er?” Peter questions. Then he blushes. “I mean —”

There is no salvaging that.

Saul steps in with, “I do worry, though, that I’ll point at someone and give them antigout, only, they’ll then have gout.”

“That’s impossible,” Bethany assures him.

“They could get a gout-like syndrome,” says Saul. “Or gout, that is saint-resistant. Like those bacteria.”

“Nobody ever proved,” says Peter, who is going to point out that it was never actually established that bacillus deuterocanonicus was saint-resistant, but Saul waves it off.

“Or those other bacteria!”

Peter makes a wry face.

“If you’re determined to bash your sainthood,” he says, “I’m hardly going to stop you. You go! You show that —”

Much as Peter would like to finish a sentence at this point, he doesn’t actually know who that would be showing.

“. . . that canonization committee?”

“The Pope,” guesses Saul, dismally. “That’s who I’d show, but I won’t show him. He will come along, instead, and he will rip the hat right off my head, and he will mock: ‘Saul! Your miracles are inefficacious.’”

“Really?” says Bethany.

“He wears a white, white hat,” says Peter.

“Oh, God,” says Bethany. “He does, doesn’t he. He’d eat you.”

They ponder this.

“Though,” says Peter, “realistically, I don’t think he has the necessary authority. This is England!”

“I can’t accept the Anglican explanation for the scissors,” sighs Saul. “That’s why I’m a filthy Papist.”

“That and the filth?” Bethany says.

“It’s hard climbing up here without anybody noticing,” says Saul. “I had to scale the trash chute!”

“There’s a stairway,” says Bethany, at which Saul’s face inevitably falls.

“I’m really bad at this,” says Saul. “Seriously. I should just go get myself a Devil hat or something. What color would that be?”

“He doesn’t wear hats,” says Peter. “He’s the Devil.”

“He could,” says Bethany, but Peter just shakes his head.

Their conversation gets boring for a while. It’s all about subtle details of color theory and ecclesiastical traditions, followed by this digression on NP-completeness that basically is just blah blah blah blah blah.

I mean, maybe in there somewhere they said the thing you’ve been waiting your whole life to be hearing. But I don’t think so.

Probably?

I mean, probably not.

“So what we do, guys?” Bethany says, after a while. She’s feeling a little bit better.

“Saint stuff,” Peter says.

“I mean,” says Bethany, but they all know what she means. She means, what is that, anyway?

So Peter just answers. “I punched the Devil once. Right on the nose!”

“Oh!” says Bethany. “Violence? I can do tha —”

She hesitates. There’s a kind of sickness churning in her chest that suggests that possibly violence isn’t central to what a saint does.

“Oh, come on,” she whispers, to the stars.

Doom darkens around her. She glares at it. But it’s just a perceptual phenomenon!

The harder she glares at it the darker it just dooms.

She rips her eyes away.

“It’s probably a moral test,” she denies. “The hat knows that we, as saints, have to be strong enough to beat up evil even after our sainthood tunes and sharpens our inner awareness that hurting people is wrong.”

“Hats don’t lie about moral issues,” Saul informs her.

“Seriously?”

Saul hesitates. He looks at his hands. “Well, they’d better not. I’d have to take mine off!”

“But I’ve got to be able,” says Peter, “to smush scissors.”

“What?”

“I can’t — I mean, it can’t be, I mean, violence can’t be wrong for me. I’m Peter.”

“You can’t reason with scissors,” Saul assures him.

“You can,” says Peter. “I just don’t want to.”

“You can?”

“You — well, I mean, not hand scissors,” says Peter. “But I could be a missionary to the scissors-swarm. If I wanted to. Which I don’t! Because they’re scissors. I mean, seriously. Nobody makes giant statues in honor of missionaries who diplomat with scissors. I want books. I want postcards. Big pictures saying, Peter:” and here he sweeps his hand to indicate how big the pictures will be. He’s imagining a glorious image of himself, there, on top of a pile of dead scissors; martyred, he, scissors in his eyes in the shape of crosses, scissors through his hands, and a glorious banner fluttering from him, and he declaims the words it reads: “He was awesome, and he did for ’em.*”

The footnote, which he doesn’t share aloud, reads: * also he was an astronaut and a ninja. So there.

“They’ve already sort of started,” says Bethany.

“Hm?” says Saul.

“They’ve started. I mean, the merchandizing and stuff. Down at the cathedral. There’s this eighty-year-old window mosaic of me blessing away some Oracle bug.”

“Huh,” says Peter. “You’d think somebody would have noticed that you hadn’t been born yet.”

“That’s cathedrals for you,” says Bethany. “They didn’t even figure out who Christ was for like four hundred years after he showed up at Dura-Europos, and I think the Vatican’s still got about five saints and a Second Coming up there that haven’t shown yet at all. You’re in front of a boot.”

“What?”

“At the cathedral. In the image. You’re there, spreading your arms and glowing with your back to a really big boot.”

“That’s just awesome,” says Peter. He can’t tell whether he’s being sarcastic or not. He likes boots, but there’s a disturbingly Mother Hubbard vibe to this idea.

“I’d actually guessed,” says Bethany, “that you’d like, bless footwear.”

“Not unless there are storms or scissors,” says Peter, “and a sea of some sort involved.”

“I wish I could still kill people,” says Bethany.

She’s thinking of Edmund.

“I wish I could kill them, and eat their hats.”

“I wish I had a pony,” says Saul.

Bethany giggles.

“I want to rule the universe,” counters Bethany, snapping her fingers and pointing at Saul. “From a giant throne in the cosmos. It’s made of lightning!”

“But my pony,” says Saul.

“No! I flippantly dispose of ponies. You shall have none. I am cruel!”

“I want to fight scissors,” says Peter.

Bethany waves a hand dismissively. “Go do it,” she says.

“It’s impossible!” says Peter. “They’re all in space!”

Bethany focuses on him.

“You’re playing this game wrong,” she tells him.

Peter makes a face. “Fine,” he says. “I wish I could ride a holy beanstalk-climbing wolf up a magical beanstalk to fight scissors. In space! And the evil aliens are there too.”

“Better,” says Saul. “I want a cure for cancer.”

“They cured cancer,” says Bethany.

“Not all of it,” says Saul.

“The Sheffield Cancer Repository doesn’t count! That thing will die if it stops being cancer.”

“Maybe it ought to die,” says Saul. “Stupid cancer.”

“Don’t be mean,” says Bethany.

Saul sighs.

“I want to be good,” he says.

Peter nods, like: I hear you.

“I want to be good,” says the saint, feebly, “but somehow — somehow I think I’m not.”